SOCIAL

Is Facebook Really to Blame for Increasing Political Division?

There is a lot to take in from the latest New York Times’ latest report on an internal memo sent by Facebook’s head of VR and AR Andrew Bosworth in regards to Facebook’s influence over voter behavior and societal shifts.

Bosworth is a senior figure within The Social Network, having first worked as an engineer in 2006, before moving on to head the platform’s mobile ad products from 2012 to 2017, to his current leadership role. As such, ‘Boz’ has had a front row seat to see the company’s rise, and in particular, given his position at the time, to see how Facebook ads influenced (or didn’t) the 2016 US Presidential Election.

And Boz says that Facebook ads did indeed influence the 2016 result, though not in the way that most suspect.

In summary, here are some of the key points which Bosworth addresses in his long post (which he has since published on his Facebook profile), and his stance on each:

- Russian interference in the 2016 election – Bosworth says that this happened, but that Russian troll farms had no major impact on the final election result

- Political misinformation – Bosworth says that most misinformation in the 2016 campaign came from people “with no political interest whatsoever” who were seeking to drive traffic to “ad-laden websites by creating fake headlines and did so to make money”. Misinformation from candidates, Boz says, was not a significant factor

- Cambridge Analytica – Bosworth says that Cambridge Analytica was a ‘non-event’ and that the company was essentially a group of ‘snake oil salesman’ who had no real influence, nor capacity for such. “The tools they used didn’t work, and the scale they used them at wasn’t meaningful. Every claim they have made about themselves is garbage.”

- Filter bubbles – Bosworth says that, if anything, Facebook users see content from more sources on a subject, not less. The problem is, according to Boz, that broader exposure to different perspectives actually pushes people more to one side: “What happens when you see more content from people you don’t agree with? Does it help you empathize with them as everyone has been suggesting? Nope. It makes you dislike them even more.”

But despite dismissing all of these factors, Bosworth says that Facebook is responsible for the 2016 election result:

“So was Facebook responsible for Donald Trump getting elected? I think the answer is yes, but not for the reasons anyone thinks. He didn’t get elected because of Russia or misinformation or Cambridge Analytica. He got elected because he ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser. Period.”

Bosworth says that the Trump team simply ran a better campaign, on the platform where more people are now getting their news content.

“They weren’t running misinformation or hoaxes. They weren’t microtargeting or saying different things to different people. They just used the tools we had to show the right creative to each person. The use of custom audiences, video, ecommerce, and fresh creative remains the high watermark of digital ad campaigns in my opinion.”

The end result, Bosworth says, didn’t come about because people are being polarized by the News Feed algorithm showing them more of what they agree with (and less of what they don’t), nor through complex neuro-targeting of ads based on people’s inherent fears. Any subsequent societal division we’re now seeing which may have come about because of Facebook’s algorithms is due to the fact that its systems “are primarily exposing the desires of humanity itself, for better or worse”.

“In these moments people like to suggest that our consumers don’t really have free will. People compare social media to nicotine. […] Still, while Facebook may not be nicotine I think it is probably like sugar. Sugar is delicious and for most of us there is a special place for it in our lives. But like all things it benefits from moderation.”

Boz’s final stance here is that people should be able to decide for themselves how much ‘sugar’ they consume.

“…each of us must take responsibility for ourselves. If I want to eat sugar and die an early death that is a valid position.”

So if Facebook users choose to polarize themselves with the content available on its platform, then that’s their choice.

The stance is very similar to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s position on political ads, and not subjecting such to fact-checks:

“People should be able to see for themselves what politicians are saying. And if content is newsworthy, we also won’t take it down even if it would otherwise conflict with many of our standards.”

Essentially, Facebook is saying it has no real stake in this, that it’s merely a platform for information sharing. And if people get something out of that experience, and they come back more often as a result, then it’s up to them to regulate just how much they consume.

As noted there’s a lot to consider here – and it is worth pointing out that these are Bosworth’s opinions only, and they are not necessarily representative of Facebook’s company stance more generally, though they do align with other disclosures from the company on these issues.

It’s interesting to note, in particular, Boz’s dismissal of filter bubbles, which are considered by most to be a key element in Facebook’s subsequent political influence. Bosworth says that, contrary to popular opinion, Facebook actually exposes users to significantly more content sources than they would have seen in times before the internet.

“Ask yourself how many newspapers and news programs people read/watched before the internet. If you guessed “one and one” on average you are right, and if you guessed those were ideologically aligned with them you are right again. The internet exposes them to far more content from other sources (26% more on Facebook, according to our research).”

Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg quoted this same research in October last year, noting more specifically that 26% of the news which Facebook users see in their represents “another point of view.”

So the understanding that Facebook is able to radicalize users by aligning their feed with their established views is flawed, at least according to this insight – but then again, providing more sources surely also enables users to pick and choose the publishers and Pages that they agree with, and subsequently follow, which must eventually influence their opinion through a constant stream of content from a larger set of politically-aligned Pages, reinforcing their perspective.

In fact, that finding seems majorly flawed. Facebook’s News Feed doesn’t show you a random assortment of content from different sources, it shows you posts from Pages that you follow, along with content shared by your connections. If you’re connected to people who post things that you don’t like or disagree with, what do you do? You mute them, or you remove them as connections. In this sense, it seems impossible that Facebook could be exposing all of its users a more balanced view of each subject, based on a broader variety of inputs.

But then again, you are likely to see content from a generally broader mix of other Pages in your feed, based on what friends have Liked and shared. If Facebook is using that as a proxy, then it seems logical that you would see content from a wider range of different Pages, but few of them would likely align with political movements. It may also be, as it is with most social platforms, that a small number of users have outsized influence over such trends – so while, on average, more people might see a broader variety of content overall, the few active users who are sharing certain perspectives could have more sway overall.

It’s hard to draw any significant conclusions without the internal research, but it feels like that can’t be correct, that users can’t be exposed to more perspectives on a platform which enables you, so easily, to block other perspectives out, and follow the Pages which reinforce your stance.

That still seems to be the biggest issue, that Facebook users can pick and choose what they want to believe, and build their own eco-system around that. A level of responsibility, of course, also comes back to the publishers who are sharing more divisive, biased, partisan perspectives, but they’re arguably doing so because they know that it will spark debate, because it’ll spark comments and shares and lead to further distribution of their posts, gaining them more site traffic. Because Facebook, via its algorithm, has made such engagement a key measure in generating maximum reach through its network.

Could Facebook really have that level of influence over publisher decisions?

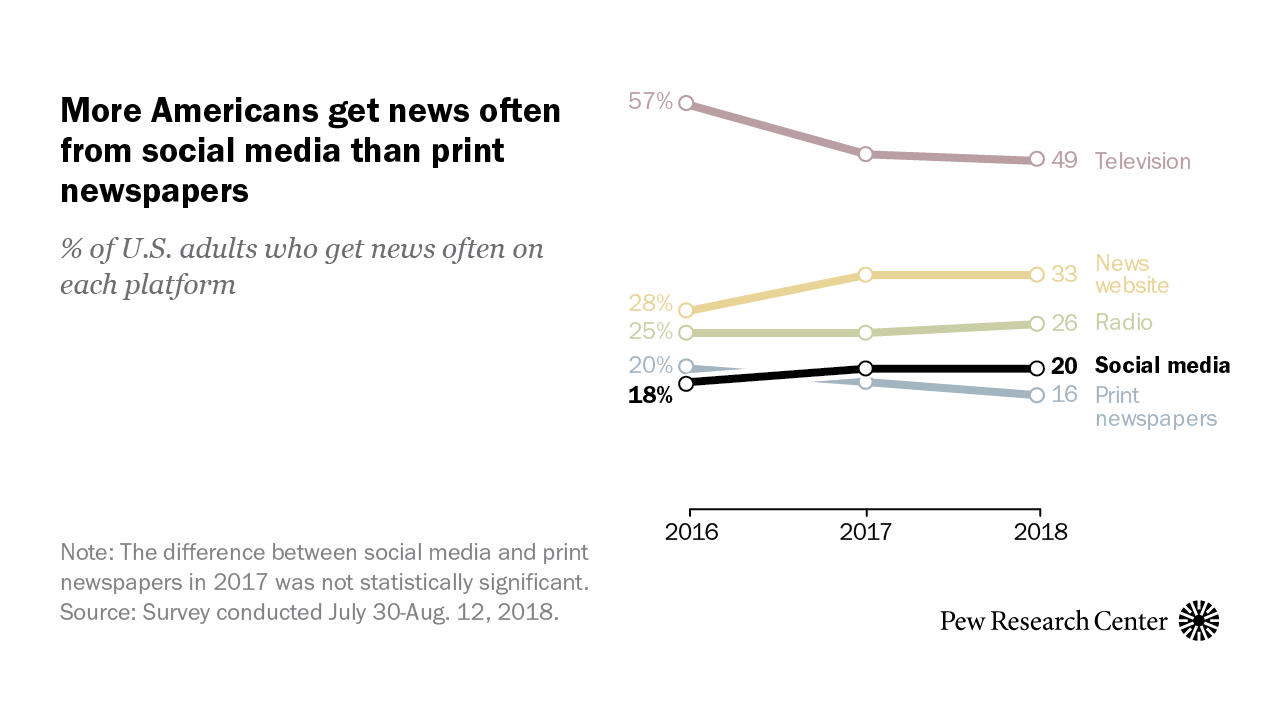

Consider this – in 2018, Facebook overtook print newspapers as a source of news content in the US.

Facebook clearly does have the sway to influence editorial decisions – so while Facebook may say that it’s not on them, that they don’t have any influence over what people think, or the news that they choose to believe, it could arguably be blamed for the initial polarization of news coverage in the first place, and that alone could have lead to more significant societal division.

But really, what Boz says is probably right. Russian interference may have nudged a few voters a little more in a certain direction, misinformation from politicians, specifically, is likely less influential than random memes from partisan Pages. People have long questioned the true capabilities of Cambridge Analytica and its psychographic audience profiling, while filter bubbles, as noted, seem like they have to have had some impact, but maybe less than we think.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that Facebook has no responsibility to bear. Clearly, given its influence and the deteriorating state of political debate, the platform is playing a role in pushing people more towards the left or right respectively.

Could it be that Facebook’s algorithms have simply changed the way political content is covered by outlets, or that giving every person a voice has lead to more people voicing their beliefs, which has awakened existing division that we just weren’t aware of previously?

That then could arguably be fueling more division anyway – if you see that your brother, for example, has taken a stance which opposes your own, you’re more likely to reconsider your own position based on it coming from someone you respect.

Add to that the addictive dopamine rush of self-validation which comes from Likes and comments, prompting more personal sharing of such, and maybe Boz is right. Maybe, Facebook is simply ‘sugar’, and we only have ourselves to blame for coming back for more.