SOCIAL

In east Ukraine, people turn to Telegram for war news

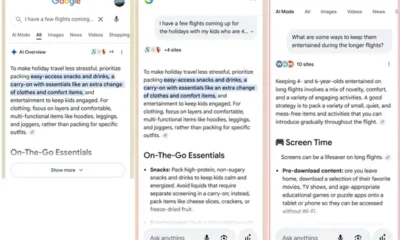

Bogdan Novak, a journalist at Pro100 media, speaks with AFP in Kramatorsk – Copyright AFP Genya SAVILOV

Anna MALPAS

Making coffee for a soldier outside a shopping centre in eastern Ukraine, 24-year-old Nina said she gets news on the war with Russia that has rocked her country from social media.

She lives in Kramatorsk, a city about 30 kilometres (20 miles) from the frontline that has been regularly hit by Moscow’s forces.

Like many Ukrainians, she has not relied on traditional media to stay informed on the dragged-out conflict since it began last February and has instead turned to Instagram, TikTok and Telegram.

“The news is on Kramatorsk Instagram accounts and on Telegram channels,” she said outside her mobile coffee truck.

The local Telegram channels she reads — called “Typical Kramatorsk” and “I love (heart) Kramatorsk” — have 107,000 and 57,000 followers respectively.

She is not alone in swiping through posts to stay up to date.

People living in the industrial city said they mostly get updates on the war from social media and personal contacts.

The frontline hub, where many speak primarily Russian, has been hit by missile attacks in recent weeks. Its supermarkets and cafes are busy with soldiers resting from the front line.

“My TV is turned off. I don’t switch it on,” Nina said as she poured a latte for a soldier. She also does not go to news websites.

As for print media, she looked blank.

“I don’t read newspapers,” she said. “It’s all electronic now.”

– ‘TV is irrelevant’ –

Older Ukrainians have increasingly also turned to social media for updates.

The 56-year-old driver of a truck collecting shattered roof tiles after a recent missile strike, Petro, said he mostly relies on YouTube.

“TV is irrelevant,” he told AFP.

“I believe Ukrainian news: about the most recent strikes, about those floods (in southern Ukraine).”

But, in a region where many do not trust authorities, 16-year-old waiter Dmytro said he also turns to Russian-language channels such as Kramatorsk 24, which has 29,000 subscribers on Telegram.

“I’ve only seen the truth about Kramatorsk on those channels, that’s why I trust them,” he said.

And while most locals mainly consume news online, some who work close to the frontline — like volunteer Bogdan — prefer to see things for themselves.

“I trust my own eyes. I don’t like reading Telegram,” the 24-year-old, who was supervising the unloading of humanitarian aid in Kramatorsk told AFP.

“As far as the Donetsk region goes… I know the situation better than the media,” he said.

“I know exactly where the front line is. Where’s dangerous and where’s not,” he added. “All only with my own eyes.”

Telegram has a simple format making it easy to see the latest developments and watch video.

But it often has little information on its authors and images are uncredited.

– ‘Not black-and-white’ –

“I Love Kramatorsk” runs regular updates on the sounds of explosions and lost pets, but is also home to posts with a clear political bias.

On Monday it described the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which has declared independence from Russian clergy, as “fake”, claiming it plans a “corporate raid” on a monastery linked to the Moscow Patriarchate.

The administrator of “I Love Kramatorsk”, who gave his name as Nikita, sent AFP a message saying he is “for freedom of speech and democracy, which does not exist in Ukraine”.

He has lived in Europe “for many years.”

Kramatorsk residents “send me the content, I just publish it”, he said.

Nikita calls himself an ethnic Russian, saying he “supports the rights of (ethnic) Russians in Kramatorsk”.

“But I distinguish ethnic Russians from Russian citizens,” he said, adding: “I don’t support what Russia is doing in Ukraine!”

“Nothing’s black and white,” Nikita said. “That’s why people read me.”

– ‘They don’t believe me’ –

Bogdan Novak, a Kramatorsk-based journalist who works for a local news site called Pro100 (Prosto) Media, said many in Donbas “don’t believe Russian or Ukrainian news.”

“I try to convey truthful information to them, but all the same, they don’t believe me,” said the 33-year-old.

He combines work as a journalist with a second job as a press secretary for a volunteer group, saying it’s “very hard to survive” as a local reporter.

But he believes freedom of speech has increased.

“We try to give information objectively,” he said.

Novak’s news site reported the same monastery story as “I Love Kramatorsk” — quoting the regional governor claiming the monks cooperated with Russian special services.

But the report also mentioned that hundreds sheltered there from Russian shelling.

Novak says he understands why people prefer brief news updates on social media to longer stories.

“They need urgent information,” he said.

“It is more convenient for them to watch videos with short text stories.”

During the war, he said there is primarily demand for information on day-to-day issues

“There will be no electricity here, no water there, humanitarian aid will be handed out here,” he said.

“That’s it. People don’t need any more information.”