Taylor Lorenz’s book, Extremely Online, tells the story of influencers and social media

The story of the internet is the story of men pouring money into platforms they don’t understand — and no one understands this better than Taylor Lorenz, the author of the new book Extremely Online: The Untold Story of Fame, Influence, and Power on the Internet, out October 3.

Over the course of the book, which spans from the early 2000s to the present, she charts the rise of blogs and the birth of social media, and specifically the ways that each platform’s power users shaped them for the better and for the worse. It offers context for questions like, “Why, to this day, can no one figure out how to reliably monetize short-form content?” and “Why has Twitter — or X, whatever — always been such a mess?” and “How come tech bros are still trying to make live-streaming happen?” Sprinkled throughout are entertaining anecdotes about why the internet looks and feels the way it is today; who knew, for instance, that part of the reason why brands demand to review sponsored content before it gets posted is because a mommy blogger once included the phrase “hairy vaginas” in an ad for Banana Republic? Or that in the early days of Instagram, Scooter Braun demanded Justin Bieber get paid for posting there? (Instagram called his bluff; he kept posting.) Or what about the group of famous Viners who asked Twitter to pay them a million dollars per year — each — to remain on Vine? (Vine died shortly thereafter; RIP.)

Having pioneered the job before most publications were paying attention, Lorenz is practically synonymous with internet culture reporting; as someone who also covers the beat, just last week I had someone compliment me on a story I wrote, except that it was actually Lorenz’s. In our conversation, we chatted about the rise of “followers, not friends,” why platforms are always clamoring for longer content, and how the FTC accidentally made sponcon cool. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You write how Silicon Valley is often portrayed as a group of brilliant, ambitious young men who can see the future, but that social media proved them all wrong. There’s a pattern in the book of men inventing a thing and women mastering and reinventing it. What are some of the ways that happened?

My book opens with the Silicon Valley version of blog culture, which was a lot of tech and political blogs, and then what women did with it, which was to create the mommy blogger ecosystem by building personal brands, commodifying themselves, and becoming the first influencers. But you see it time and time again — Julia Allison, who was one of the first multi-platform content creators and did what she called “life casting,” would document her outfits, link to things, use affiliate links for revenue generation, and had a YouTube show. The version of social media that the tech people envisioned was turned on its head and very quickly subverted by a lot of really creative and entrepreneurial young women and other marginalized people who ultimately were really disrespected.

For most of the history of social media, Silicon Valley has been incredibly hostile to these power users. [Tech founders] almost resented the power they had on the internet. Once the pandemic hit, they all started talking about the “creator economy” like it was some new thing. They’d maligned it for decades, because it primarily was pioneered by women.

What made the perfect storm for mommy bloggers to really explode during that time?

You had a lot of things happening at once: a super misogynistic traditional media climate, where women’s magazines in the late ’90s and early 2000s didn’t discuss any of the realities of motherhood, and you had these Gen X mothers who were working, they were educated and more progressive than their parents, and living in double income households who were like, “This version of motherhood doesn’t resonate with me at all. I’m gonna turn to the internet and use it as an outlet to talk about how it really is. It’s messy, and it’s hard. Sometimes I hate my husband, and I hate my children, or I can’t breastfeed, or I’m deeply depressed because I have postpartum depression.” The whole idea of the “wine mom” was born out of this era, because a lot of moms talked about turning to substance abuse and were struggling. These things were normalized by the women talking about it.

It also helped that it was text, because a lot of them didn’t even use photos of their children, or used pseudonyms. They were breaking down barriers and normalizing frank discussions about really taboo topics, and it forced the legacy media to adapt and evolve, although they still haven’t totally caught up. But in terms of public discussions of motherhood, now we know postpartum depression exists, and that not all women can breastfeed. It was this perfect timing of the new generation of mothers, the blog ecosystem being born, and then this super patriarchal traditional media.

Looking back now with what we know about online platforms, it’s kind of shocking that MySpace lost out to Facebook, when MySpace was so bullish on internet stardom. Why did it take so long for Facebook to recognize the power of internet creators and people’s hunger for online fame? And what made them finally lean into it?

I think MySpace was just way too early. For most people, it was not normal to go on the internet and post about yourself. And there wasn’t this follower-based model of social media yet; it was double opt-in, so you had to befriend someone and they had to befriend you.

Facebook was a bridge platform, basically, which is why I think it’s not relevant anymore, because it didn’t lean hard enough into creators until it was too late. Facebook is sort of the epitome of the sanitized, corporate Silicon Valley version of social media. But the Facebook News Feed played such a pivotal role in influencer culture, because it taught everyone to post for an audience.

Instagram ended up being their creator strategy, because Facebook just fumbled the bag so many times. Let’s not forget that when Vine was flailing and all the creators left Vine, before they went to YouTube, they went to Facebook. Facebook Video had all those people, and they squandered it. They had the biggest of all the biggest YouTubers and they couldn’t get the monetization right. They didn’t care about creator monetization, but YouTube had built that out, and they were just in such a better position to absorb that talent.

Why was YouTube early to embrace creators?

What’s crazy is that YouTube could have gone a different way. They saw very early on if they allowed people to make money, that would keep talent there. YouTube was also adjacent enough to the entertainment world where there were standards around paying for content and ad deals. YouTube started as an online video platform, and there were ad models in place for online video, like pre-roll or mid-roll. With Facebook, which was more text-based social media, there wasn’t a norm, there weren’t revenue models, and there weren’t monetization pathways already established. You saw a lot of struggle, like, “Who’s gonna crack monetization?” And actually, no one has cracked it. Look at Twitter. Short text updates are just much harder to monetize.

Why did influencer collab houses keep coming up and then dying out? Do you think they’ll ever come back in a big way?

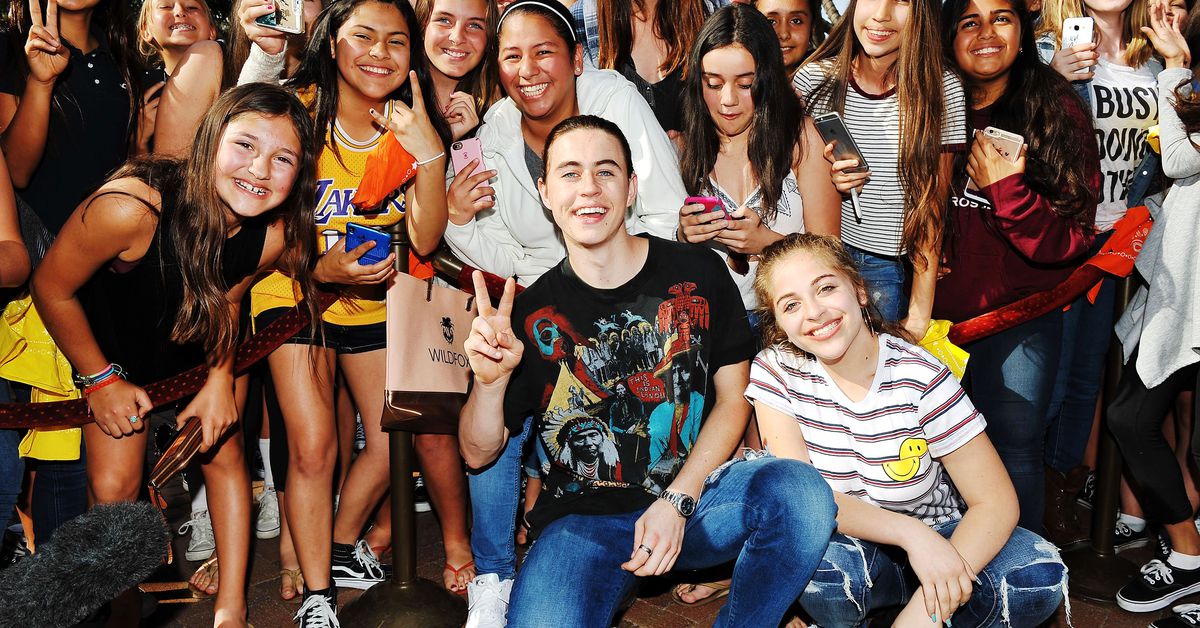

Creative young people have always lived together. The Station was the first true content house, because for early internet creators collaboration was so crucial. It was like the primary vehicle for growth because we didn’t have algorithmic discovery mechanisms like we have now. So if you were living in a house and you were constantly collabing with a bunch of people, suddenly you’re following them. Gen Z kids grew up watching the Station and the FaZe Clan house, and then I think they immediately wanted to replicate it on TikTok. But then it got very professionalized, like they started as content creators living together, there was no management company that was trying to extract profit from them, or a brand that was involved or whatever.

Once people started to pay attention to content creators in 2020, all these brands and management companies started these content houses, and that business model failed very quickly, because it’s such a huge liability running a house full of kids. These houses are sort of inherently ephemeral, because certain people become more famous, certain people move on. It’s like being part of a frat — you’re not gonna live there forever. I also think that discovery has changed, so you don’t need to necessarily be living together in the same place to get discovered on YouTube, because we have TikTok and algorithmic discovery handles all of that. The pace of fame is so different: it’s so much faster.

It’s so funny seeing how early Instagram was so explicitly anti-advertising, even anti-self-promotion, when that’s literally the thing we think about when we think about Instagram. Instagram’s community guidelines once even read, “When you engage in self-promotional behavior of any kind on Instagram it makes people who have shared that moment with you feel sad inside … We ask that you keep your interactions on Instagram meaningful and genuine.” But you argue that this inadvertently invented the concept of the “sponsored post.” How did that happen?

They tried to keep it free of advertising while also allowing people to build big followings and spurring that with their “suggested user” list; they created this vehicle for sponsored content. Suddenly, brands desperately wanted to reach people on Instagram, but there was no way to advertise. So they went directly to the creators. That happened very early on: some of the earliest stuff on Instagram was sponsored content, it just wasn’t disclosed or clear what it was. When [Instagram] rolled out ads later, it was like, you couldn’t put the genie back in the bottle. They ended up kind of shooting themselves in the foot because we live in a hyper-capitalist society and everyone has to make money. These content creators recognized the value of fame and attention, and online brands are going to want to reach that audience. I think it was Instagram’s mistake not to realize it sooner and build out some way to facilitate brand deals between creators and big companies because they could have built a really sustainable revenue model around it. They didn’t.

When the Federal Trade Commission sent all those warnings to creators who didn’t disclose sponsored content, everybody thought that would be the end of influencing. Instead, the opposite happened. Why?

It’s so funny to read articles from that time. They’re gleeful, like, “This is the end of influencers.” Once again, it’s people not understanding how the internet works and not anticipating regulators coming in. It was like gasoline on a fire: What it did was it actually normalized sponsored content and made it aspirational.

At the same time, you also had this very specific genre on YouTube where everyone was doing pranks and staged drama — why did YouTube incentivize those things?

This was like peak daily vlogging, when [YouTube] started to reward people who posted more frequently. Casey Neistat really kicked this off, but it was embraced by Vine creators, who leaped off Vine onto YouTube and brought their publishing schedules with them. That was how they grew — they had to constantly think of content, but there’s no way to create 24/7 interesting, engaging organic content. Nobody’s life is that interesting. So you had to stage a lot. You had to always up the ante and make things more and more extreme to get attention because it was so competitive, because everyone was posting every day. I think that’s what led to this prank culture. A lot of it also came from Vine — they were a new class of creators who were ridiculous men, and they brought that energy to YouTube and then YouTube incentivized it. Things got very out of hand really quickly.

This seemed to lead pretty directly to the Adpocalypse, when YouTubers became liabilities because they kept producing increasingly extreme content for views. What ripple effects did that have on the wider creator economy?

Advertisers were thrilled to reach people on YouTube. They were pouring tons of money into YouTube, and they weren’t thinking about it because internet culture at this point was so secondary to mainstream pop culture. The mainstream media did not pay attention to it at all aside from tabloids, and their coverage was very promotional.

Suddenly, in 2017, a lot more criticism was focused on tech. You had Trump sworn in, and everyone started to look at these platforms and start to question, “Wait a minute, are these platforms good, or are they bad?” People actually started to pay attention to what was going on on these platforms. [There was] that Wall Street Journal story about PewDiePie, the biggest YouTuber, and you saw the mainstream media doing hard reporting and looking into it and being critical. That led advertisers to freak out and pull all of their dollars, and it really hurt a lot of creators. The biggest content creators, like the Logan Pauls and the PewDiePies of the world, ultimately were totally fine. But it did wipe out and harm a lot of mid-level and small creators, because they suddenly didn’t have the advertising revenue that they had previously. I think that made a lot of YouTubers very hostile to the media, because they always blamed the media for that. Everyone I interviewed was like, “Well, if the media didn’t write these stories and get all inflammatory…” and it’s like, no, if YouTube didn’t incentivize this content.

The Adpocalypse and algorithm changes and the pressure of posting every day made a lot of creators ultimately quit altogether. What I’m wondering is — did the platforms even care? Like, did that even affect YouTube’s bottom line? Or were they secretly kind of happy about it?

YouTube ultimately did not do very much. They’ll probably claim that they did, but they really didn’t look at how burnt out everyone was. Today everyone’s just as burnt out, if not more, because now they have to make [YouTube] Shorts content. But I do think it was the first recognition that this job is incredibly hard on your mental health. People had talked about it, but it wasn’t really a public discussion until then. That was also when you saw a lot of “I’m leaving BuzzFeed videos,” remember? Everyone just started to be like, “Wait a minute, this is so hard, and I’m actually depressed, and this isn’t the dream you think it is.”

With that conversation, there started to be an acknowledgment of the labor behind it. You started to see people take it more seriously, but unfortunately, a lot of creators got chewed up and spit out and there was no lasting change and the Internet chugged along. And that’s how it always goes, right? The internet destroys people’s mental health every day, and we’re not changing the system. If you take a week off, there’s people that will replace you. It’s not like there’s a shortage of people posting online. That’s why companies sell this illusion that anybody can make it on the internet and anybody can be the next Mr. Beast, because they need people to believe that so that they keep posting and investing and making things for their platform.

You end the book with a call for people to learn from the last 20 years of internet culture. What are the most important lessons, now that we’re in this world where everyone is encouraged to be a creator of some kind or already is?

Another theme of my book is this notion of users seizing more control over platforms, and I do think we actually have an enormous amount of collective power over them. It’s always a push-and-pull dynamic, but these platforms have shown that they are responsive to public pressure time and time again. If we want better platforms, we need to hold them accountable and force change, because they’re never going to change unless we make them. [We need to] build better spaces online that are less profit-driven and horrible.

Another theme is online misogyny, and I hope people can reexamine this recent history of the internet and look at women, who pioneered all this amazing stuff and never got credit and never saw the upside. Misogyny and hate are so pervasive and I just hope that people can read it and recognize how we got to where we are.

I’m very against the notion that logging off is good for your mental health. There’s this idea that our phones and the internet are destroying everything and making us miserable. I think that’s not true. It’s the platforms, but it’s not the internet as a whole. If you look at what the internet facilitated — the good parts of the internet — it’s a tool for human connection. I don’t think we want to live in a less-connected world, because then you have institutions with an enormous amount of power, and it sucks. I think we just need to build a more positive internet and build better platforms to spend time on, but I don’t think people should retreat away. Connection is valuable. We all want connection, we all want validation, and that is what the internet can provide. But we need these hyper-capitalist, monopolistic tech platforms to get out of the way.

This column was first published in the Vox Culture newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.