SECURITY

Zuckerberg Disputes Facebook’s Role in Societal Division at Munich Security Conference

In the wake of the 2016 US Presidential election, social media – and Facebook specifically – has been blamed for causing increased angst and societal division, with the spread of ‘fake news’, foreign interference, filter bubbles and more, all reportedly being exacerbated by the rising use of social apps.

But is that true? Does Facebook really play such a significant role in the modern news dissemination process that it now has the power to shift the opinion of the electorate – or are we just looking to append blame for divisions that have always existed?

The latter is where Facebook is now leaning, and late last week, at the Munich Security Conference, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg provided a few rebuttals on suggestions that his platform has been the cause of such concerns.

“We take down now more than a million fake accounts a day across our network. […] The vast majority are not connected to a state actor trying to interfere in elections, they’re a combination of spammers and people trying to do different things.”

“People are less likely to click on things and engage with them if they don’t agree with them. So, I don’t know how to solve that problem. That’s not a technology problem as much as it is a human affirmation problem.”

On echo chambers:

“The data that we’ve seen is actually that people get exposed to more diverse views through social media than they were before through traditional media through a smaller number of channels.”

The latter comment relates to study which has also been referenced by Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg and former Facebook mobile ads chief Andrew Bosworth – in an internal study to examine the impacts of filter bubbles, Facebook found that 26% of the news content that users see in their Facebook feeds represents “another point of view”, which makes them significantly more likely to be exposed to more perspectives on Facebook than they would via traditional media distribution, as opposed to narrowing their scope.

So Facebook’s not to blame – foreign actors seeking to manipulate voters have not been a major influence on voting behavior, Cambridge Analytica was a ‘non-event‘, misinformation from candidates was not “a major shortcoming of political advertising” on the platform in 2016 (hence Facebook’s decision to exempt political ads from fact-checks in 2020), people are not having their established views reinforced by Facebook’s algorithm showing them more of what they agree with, and less of what they don’t.

Facebook, in this respect, doesn’t see itself as being a cause of societal division – but then again, Zuck and Co. may be neglecting a significant part of the equation, of which Facebook is indeed playing a major role.

In a leaked internal memo, which The New York Times got access to last month, Facebook’s now head of VR and AR Andrew Bosworth noted that while users are exposed to more perspectives on Facebook, that’s not necessarily a good thing:

“Ask yourself how many newspapers and news programs people read/watched before the internet. If you guessed “one and one” on average you are right, and if you guessed those were ideologically aligned with them you are right again. The internet exposes them to far more content from other sources (26% more on Facebook, according to our research). This is one that everyone just gets wrong. The focus on filter bubbles causes people to miss the real disaster which is polarization. What happens when you see 26% more content from people you don’t agree with? Does it help you empathize with them as everyone has been suggesting? Nope. It makes you dislike them even more.”

This is a significant admission that many overlooked – here, Bosworth is saying that Facebook knowingly exposes its users to a lot more content that they disagree with, which subsequently solidifies them further within their own, entrenched beliefs.

Why would Facebook do that? If Facebook knows that users are only going to become more angry when they see more posts that they disagree with, why would Facebook allow this to happen?

This finding, from a study into what makes content more shareable online, conducted back in 2010, could have something to do with it:

“The results suggest a strong relationship between emotion and virality: affect-laden content – regardless of whether it is positive or negative – is more likely to make the most emailed list. Further, positive content is more viral than negative content; however, this link is complex. While more awe-inspiring and more surprising content are more likely to make the most emailed list, and sadness-inducing content is less viral, some negative emotions are positively associated with virality. More anxiety- and anger-inducing content are both more likely to make the most emailed list. In fact, the most powerful predictor of virality in their model is how much anger an article evokes.”

Anger is the most powerful predictor of virality – so content which incites anger is the most likely to be shared online.

For Facebook, engagement is everything – connecting more users to content that sparks engagement, through comments, Likes and shares, is the key focus of Facebook’s News Feed algorithm. The impetus for Facebook is clear – the more engagement it can generate, the more time people spend on its platforms, and the more ads it can then show them while they’re there. And while using anger as the lure may seem like a risk, because people, you’d assume, will eventually get fatigued and stop logging on, the findings in the above survey actually perfectly align with what most people see in their Facebook feeds.

Inspirational quotes, stories of people overcoming the odds, video tales of street dogs and cats brought back to health – these types of positive stories do well, and regularly gain traction in the Facebook ecosystem. As do the opposite – anger-inducing reports of political controversies, which spark masses of responses, and trigger furious debates in the comments.

Facebook knows that these types of posts do well, and if it can maintain the balance between showing you a little of each every time you log on, you’ll probably keep coming back.

So while Facebook might be looking to avoid the blame for increasing societal divides, it actually has a lot of incentive to provoke such, and keep provoking them in order to keep you interacting. Again, anger is the most powerful predictor of virality. And Facebook, very clearly, knows this.

But of course, it doesn’t stop there – with social media now outpacing print newspapers as a key news source in the US, and more Americans now getting news content from Facebook specifically, the publications themselves have had to adjust. Most publishers now get a significant amount of their revenue from online distribution, primarily through ads – and in order to maximize ad clicks, and expose more people to more ad content, the publications themselves have also learned what goes viral and how that can get them more attention.

In this system, the publications are also incentivized to produce more divisive, partisan content, because again, that’s what sparks engagement, sparks shares, and what ultimately gets more people to click through to their sites. The whole online media chain is largely built around fueling division – so if you’re wondering, after the results of the 2020 US Presidential Election come in, why this candidate did so well, and that one did so poorly, this is more likely where you should be looking.

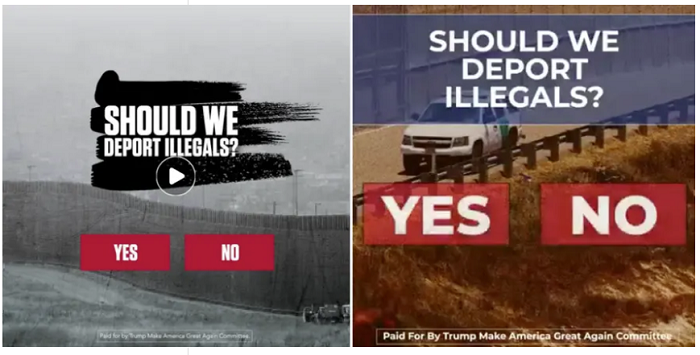

So what does that mean for political candidates? Well, there’s a reason why the Trump campaign spent $20 million on Facebook ads in 2019 alone.

As noted, ads which spark anger see more engagement on Facebook, so using divisive political messaging like this is extremely powerful for the Trump campaign. In this sense, political organizations would likely see more success by adopting a similar playbook – taking a firm stance on one side of an issue, simplifying it into a singular message, and accepting that some people are going to be upset, and dislike you because of it. Those who agree will be more solidified in their support by seeing the responses it generates, while those opposed probably weren’t going to vote for you anyway.

In the Facebook age, simplifying the complex in political messaging is key, and emotional response is the surest path to achieving cut-through, even if it does come with the risk of dividing the electorate.

You could take a similar stance in social media marketing for brands – already, various surveys and reports have indicated that younger audiences feel more aligned to ‘socially conscious’ brands, with 68% of Gen Z consumers expecting brands to contribute to society.

But is that because more brands are doing so, or because the ones that are are sparking more engagement with their content, expanding their brand awareness and solidifying their base of support.

For example, if you were to create the below two variations of a deodorant ad:

Which do you think would perform better on Facebook, based on the above overview?

The one on the right would ‘trigger’ more people, and likely prompt significantly more response. Whether that would result in more sales is another thing, but with strong links between brand awareness and sales, it could be worth the risk – granted, of course, that such political messaging is, in fact, in line with a stance that your business wants to adopt. Either way, it’s a big jump to take.

It also further underlines the point – while playing into the psychology of social sharing could help you get more traffic, it also, again, adds to underlying societal division. That’s not a good thing, but the motivations behind such are evident.

So how do you fix it? That’s a far bigger challenge – if you were to remove Facebook from the equation, other platforms would still exist, other sources would take its place, and the broader shift in online news distribution, and the motivations for gaining traffic, would still remain. While there remains an incentive to drive division, and use anger to spark engagement, such problems will persist – and as more and more content consumption shifts online, it’s hard to see it becoming less of a problem any time soon.

But in considering your own behavior, whenever you go to comment, to share, whenever you go to say something about the latest controversy online, it’s worth noting the impetus behind such.

The response that you feel in that moment was the entire aim of the post, comment or ad. So how do we get more people to reconsider anger in the face of blatant provocation?