MARKETING

Twitter Releases New Political Ad Policy Following Announcement of Ban on Political Ads

Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey was heavily praised last month when he announced, in no uncertain terms, that Twitter would ban all political advertising on its platform.

We’ve made the decision to stop all political advertising on Twitter globally. We believe political message reach should be earned, not bought. Why? A few reasons…????

— jack ???????????? (@jack) October 30, 2019

This followed a speech from Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, in which he defended his platform’s decision not to subject political ads to fact-checking, under the guise of ‘voice and free expression‘ – i.e. letting the people decide what’s true and what’s not from political candidates. By comparison, Dorsey’s stance was a welcome relief, a social platform CEO who was willing to take a stand.

But even as Dorsey announced it, others – like Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren, and Instagram chief Adam Mosseri – questioned how it might actually work in practice.

This is one of the key issues many miss about banning political ads on any platform. You can’t ban these ads without significantly inhibiting the ability of activists, labor groups, and organizers to make their cases too. https://t.co/YjIgKsVDyJ

— Adam Mosseri (@mosseri) November 5, 2019

Now, Twitter has released its full, revised political ads policy, which doesn’t go as far as initially suggested, but does seek to limit the use of Twitter ads for political campaigning.

First off, Twitter says that it will prohibit the promotion of political content, with “political content” defined as:

“Content that references a candidate, political party, elected or appointed government official, election, referendum, ballot measure, legislation, regulation, directive, or judicial outcome. Ads that contain references to political content, including appeals for votes, solicitations of financial support, and advocacy for or against any of the above-listed types of political content, are prohibited under this policy. We also do not allow ads of any type by candidates, political parties, or elected or appointed government officials.”

Which seems petty clear-cut – but what about the noted conflict between political campaigning and activism by non-politically affiliated groups?

For this element, Twitter has also launched a new ad category called ‘Cause-based advertising‘.

Under its ’cause based’ banner, Twitter will allow for restricted promotion of ads that:

“Educate, raise awareness, and/or call for people to take action in connection with civic engagement, economic growth, environmental stewardship, or social equity causes.”

These ads cannot be used to “drive political, judicial, legislative, or regulatory outcomes”, and advertisers will need to be certified to run such promotions.

Twitter will also limit the targeting capacity of any such ads:

“Targeting is restricted and limited to geo, keyword, and interest targeting. No other targeting types are allowed, including tailored audiences.

- Geo-targeting may only happen at the state, province, or region level and above. Zipcode level targeting is not allowed.

- Keyword and interest targeting may not include terms associated with political content, prohibited advertisers, or political leanings or affiliations (e.g., “conservative,” “liberal,” “political elections,” etc.).”

Additionally, news publishers who meet Twitter’s exemption criteria will be allowed to run ads that reference political content and/or prohibited advertisers under its political content policy, “but may not include advocacy for or against those topics or advertisers”. So publishers can promote their coverage of the news, but not opinion pieces which advocate for a specific political angle.

That’s quite a few exceptions, a lot of wrinkles and potential gaps that Twitter will need to work out.

As noted by Will Oremus of OneZero:

“What it all means is that Twitter will now be in the business of divining the primary goal of every advertiser who places an ad that might have political ramifications, and deciding which ones will be allowed and which won’t. If that sounds hard to do in the United States, where Twitter is headquartered, imagine the difficulty in applying it to every country in which Twitter operates.”

And that really is a key consideration. The big focus here is obviously the upcoming US Presidential Election, but in 2020, there are also major polls happening in Egypt, France, Serbia, Brazil and many more. Even if Twitter does have a team equipped to manage and decide on US election ad approvals, based on these parameters, will it have the same capacity to handle all of these separate polls? Is it possible for Twitter to actually enforce these regulations in a uniform and balanced way across every election in every region?

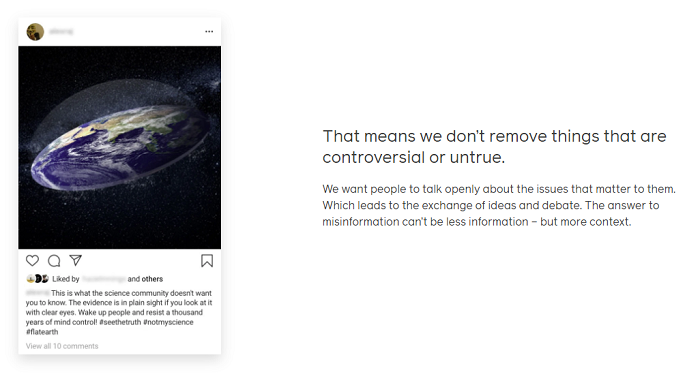

It seems like a very difficult task – which is partly why Facebook has decided not to undertake it. Another, more skeptical view is that Facebook has less interest in removing divisive, debate-worthy content of this type because it fuels on-platform engagement – in a recent Facebook overview of its policy decisions on such, it included this fake news story as an example of content it won’t remove.

That post, by any scientific measure, is misinformation, and by allowing it, Facebook, and other platforms, enable such questioning of established facts to germinate. So should it take a stronger stand? And if it did, what impact would that have on Facebook engagement overall?

Would Facebook stand to lose out, with users then switching to other platforms to share such theories and false facts, and their related discussion?

There does appear to be some logic to the idea that Facebook may not be so interested in enforcing rules against political misinformation because of the higher levels of on-platform engagement it facilitates, and in this respect, Twitter deserves additional praise for even attempting to block the same. The impacts of removing political advertising on Twitter will not be the same as they would be on Facebook (Twitter made $3 million in revenue from political ads around the 2018 US Midterms, while Facebook has projected that US political ads would make up around 0.5% of its 2020 revenue, equivalent to around $428 million). But still, it’s a difficult task, and one which is going to open up Twitter to a lot of scrutiny, while also potentially hurting engagement.

The fact that they’re even attempting such is worthy of praise.

How effective Twitter’s bans will be remains to be seen, but Twitter has said that this is just the first step, and that it expects to learn as it goes, and build out more detail, especially for international markets.

It’s an ambitious attempt to address one of the core issues leveled at social media in recent times – and if it works, it may set a new precedent for dealing with the same on other platforms.