SOCIAL

Understanding Facebook’s News Ban in Australia, and What it Means for the Platform Moving Forward

Facebook threw the cat among the proverbial pigeons this week when it announced, after months of tense back and forth, that it would cut Australian news publishers off from its service, rather than adhering to the Australian Government’s proposed Media Bargaining Code.

I’m actually in Australia, so I can tell you how it’s going. It’s a mess. Some people still have access to news Pages in the Facebook app, some don’t. Some elements aren’t working like they should – Creator Studio, for example, seems to have freaked out entirely, though hard to tell whether that’s because of the changes in who can and can’t access certain content or just a CS problem.

But above all there, there’s a lot of confusion.

You see, most regular people haven’t paid much mind to the Government’s Media Bargaining changes, which take aim, specifically, at Facebook and Google. Why them? Because they make so much money, so the Government, based on the findings of the ACCC, decided that they should share it.

But in this instance, no matter how you might feel about Facebook in general, The Social Network is actually in the right. Here’s a look at some of the most common questions about the change in Australia, and what it might mean for similar proposals moving forward.

What is the Media Bargaining Code?

The full history of the Government’s proposed Media Bargaining Code goes back a few years.

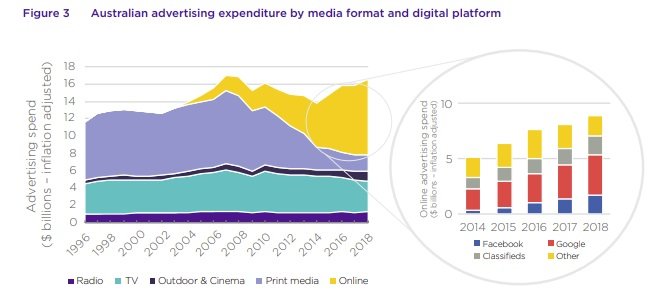

Back in 2017, the Government called on the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) to “consider the impact of online search engines, social media and digital content aggregators on competition in the media and advertising services markets.” The ACCC’s research, which it undertook over the proceeding two years, highlighted several key concerns and impacts to the local media sector, including a decline in business incentive to cover essential elements of news reportage.

“[We’re seeing] reduced production of particular types of news and journalism, including local government and local court reporting, which are important for the healthy functioning of the democratic process. There is not yet any indication of a business model that can effectively replace the advertiser model, which has historically funded the production of these types of journalism in Australia.”

This was the first seed of the Media Bargaining Code, implementing a new mechanism to fund journalism, while the ACCC’s report also took specific aim at Google and Facebook, and their dominant, and conflicted, market position.

As per the report:

“Where Google’s and Facebook’s business users are also their competitors, there are questions about whether there is a level playing field, or whether they have the ability to give themselves advantages by favouring their own products. As Google and Facebook continue to expand into adjacent markets through acquisitions and organic expansion, these risks increase.”

So the concerns relate to both Google and Facebook’s dominance, and their capacity to tilt the digital advertising field in their favor. Which are valid concerns, but how you go about addressing them is another matter.

Stemming from the ACCC’s initial findings, the Government first sought to target the tech giants via tax reform. In 2018, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced that Australia would look to squeeze more tax payments out of Google and Facebook, along with Apple and Amazon, but that plan was quashed by the Trump Administration, which made it absolutely clear that it would not stand for US companies facing higher tax obligations.

As outlined by then US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin

“The United States remains opposed to digital services taxes and similar unilateral measures. As we have repeatedly said, if countries choose to collect or adopt such taxes, the United States will respond with appropriate commensurate measures.”

The threat of a trade war with the US was enough for the Australian Government to abandon the idea completely, which meant it had to go back to the drawing board to work out how to extract more cash from the two platforms, and even the field for local media players.

That lead to the Government calling on the big tech platforms to negotiate with local media businesses, voluntarily, on a “fair and reasonable” payment model for the use of news content on their platforms. Facebook and Google both opted not to participate in this process, arguing that they gleaned little to no benefit from such content – and in fact, they actually drove benefit for news organizations by hosting links to their material.

In April 2020, amidst the rising industry impacts as a result of COVID-19, and after months of waiting on Google and Facebook to come to the bargaining table, Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg then directed the ACCC to develop a mandatory code “to address bargaining power imbalances between digital platforms and media companies”. That set the Government’s position – Google and Facebook would be forced to pay a portion of their revenue to local news publishers, by law, which then started the chain of events leading to this week’s stand-off.

The Government’s ambition here has merit, but the path they’ve taken to get there is something of a shortcut.

What’s the Australian Government asking for?

Under the Government’s Media Bargaining Code, Facebook and Google will be required to share revenue with Australian publishers for any use of news content, including links to their sites. How much, exactly, they would need to provide for this is not specified, but it would come down to negotiation between the relevant parties, and arbitration, if deals cannot be reached.

The Code also stipulates that the platforms would have to:

“…provide registered news business corporations with advance notification of planned changes to an algorithm or internal practice that will have a significant effect on covered news content.”

So anytime Google or Facebook are looking to change their algorithms, they’d need to give Australian news publishers advanced notice. But not all publishers.

In order to qualify as a news publisher within the definitions outlined in the code, an organization needs to have an annual revenue “above $150,000 in the most recent year or in three of the five most recent years”. That limits the publishers that are able to benefit from the payments.

The penalty for not adhering to the code is a maximum fine of $10 million per year, or a portion of the company’s annual revenue.

The idea, then, is that this funding would then prop-up local news publishers, and create a more level playing field by reducing the dominance of the big players.

Why doesn’t Facebook just pay up?

Well really, why should it?

As Facebook has explained repeatedly in its responses to the Australian Government.

“[The code] would force Facebook to pay news organizations for content that the publishers voluntarily place on our platforms and at a price that ignores the financial value we bring publishers.”

Facebook doesn’t have a dedicated news platform in Australia, so it drives no direct benefit from news content. Sure, Facebook does benefit from having news content on its platform, and the subsequent engagement and discussion it generates, but Facebook itself doesn’t re-share news content, it doesn’t take publisher material and re-use it for its own gain. Users, including the publishers themselves, post the content to Facebook, the latter case using Facebook’s scale to drive more traffic back to their sites.

And now Facebook has to pay them for the privilege?

Facebook has also repeatedly noted that news content, especially from Australian, publishers, is not a major element on its platform.

“For Facebook, the business gain from news is minimal. News makes up less than 4% of the content people see in their News Feed.”

But Australian publishers have pushed forward in their negotiations under the assertion that news content is, in fact, critical to Facebook, that Facebook needs their work to fuel its engine. Again, Facebook has told them, over and over, that this is not the case, and that, if anything, it’s the other way around.

“Last year Facebook generated approximately 5.1 billion free referrals to Australian publishers worth an estimated AU$407 million.”

That’s even more relevant in the case of smaller publishers who won’t benefit from the Code, and who’ve built their business models on the back of Facebook. Larger media players may be able to live without Facebook referral traffic, but the minnows may not. So again, the way Facebook sees it – and the way it is – is that Facebook doesn’t need news publishers, it’s more the other way around. And it shouldn’t have to pay for playing that role.

Given this, Facebook’s response this week should not come as a surprise.

As Facebook noted in August last year:

“Assuming this draft code becomes law, we will reluctantly stop allowing publishers and people in Australia from sharing local and international news on Facebook and Instagram.”

Facebook has been warning of this outcome for months, the move should come as no surprise.

Worth noting, too, that in the day following Facebook’s decision, traffic to Australian news sites from visitors outside the country dropped by 20%.

Why did Google pay then?

Earlier in the week, Google agreed to new deals with three of Australia’s biggest publishers which will see Google feature their content in its News Showcase offering. Those deals are said to be in the tens of millions each, which is significant – but as far back as October, Google was offering News Showcase as an alternative way forward, in order to provide additional funding for local journalism while also driving direct benefit for Google. Google has already committed $1 billion to its News Showcase product.

As Kara Swisher notes in the New York Times, there’s more at stake for Google here, so while it appears to have relented somewhat, and paid more than it was likely intending in order to get Australian publishers on board, the final arrangement is largely in line with Google’s alternate offering. It has not, it’s worth noting, agreed to adhere to the Media Bargaining Code.

And it may not have to – in welcoming the Google deals, Frydenberg has noted that:

“If commercial deals are in place, that changes the equation.”

The implication here is that the additional requirements, like sharing algorithm insights, will now not be pursued, because Google has made independent, commercial deals with publishers.

Which begs the question, what was the real intention of this policy?

Was it to level the playing field, as per the Government’s original stated intention, or was it just to extract more money from Google and Facebook? And will it really benefit ‘journalism’ as whole, or just the big players like News Corp – which, incidentally, also pays virtually no tax in Australia?

Given the process, whether you like Facebook or not, the company’s stance seems logical at this stage.

Ongoing, the further impact for Google, in potentially paying more for its News Showcase deals in Australia (we don’t have insight into the full details of Google’s negotiations with different publishers) could be that it ends up driving up the costs of similar deals in other regions, which are also pushing for greater revenue share for local news outlets. That could end up being a costly concession for the search giant.

But Facebook has also blocked Pages that aren’t news sites…

As many have noted, Facebook has also blocked a range of government and other informational Pages which are not news providers as part of its Australian blockade – it’s even blacked out its own Page.

This is true, but it’s not because Facebook has been overzealous in its approach, as many have suggested.

As per the wording of the Code, news content is classified as:

“Content that reports, investigates or explains issues or events that are relevant in engaging Australians in public debate and in informing democratic decision-making; or current issues or events of public significance for Australians at a local, regional or national level.”

Which covers pretty much every website that’s not a business – any Facebook Page that publishes information, that’s of relevance to anyone, could come under this umbrella. So Facebook cut them all off, and now it’s working its way back through certain exceptions – which really probably still fall into this category, depending on how you read it.

So don’t blame Facebook on this front, blame the code, which is overly broad and general in its scope.

People are going to turn on Facebook

Yeah, this is the gamble that Facebook’s taking, and it may well backfire – but it’s also their gamble to take.

Facebook would have some idea of the potential impacts here, it’s likely conducted tests reducing news content in Australian news feeds to examine behaviors. It could end up losing users in Australia as a result, and it’ll be interesting to see how that plays out, and what the impacts of a news-free Facebook could be on engagement trends.

But make no mistake, the Australian Government is using two multinational corporations to boost its own agenda, and sway voter opinion in its favor.

The public will never side with billion-dollar organizations that are taking money out of the country, they will always be the bad guys. The Government knows this, so it’s a safe bet to push them and see what it can get. If the companies relent, the Government wins, and if they don’t, they end up looking like the creeps, while subsequently framing the Government as the ones standing up for the rights of local businesses.

And what can the Government get? More money for the press, particularly Rupert Murdoch’s NewsCorp, which dominates the Australian news media landscape, and clearly aligns its coverage with the sitting Liberal party.

In an election year, the Government will need all the good press it can get, and it can now claim to have handed them billions in additional, potentially securing ongoing favor.

As noted, the original intentions of this proposal make sense, and there does need to be some level of balance restored in the sector. But the new Code is not about economics. It’s a lesson in modern politics, and holding government at all costs.

What happens now?

So what comes next? It still seems – or at least feels – likely that, eventually, Facebook and the Government will come to an agreement and things will go back to normal in the Australian market.

Frydenberg has already noted that talks with Facebook are ongoing, while Facebook has said that the ball is now in the Government’s court, and that it won’t be changing its stance on the Media Bargaining Code. But the blockage will put increased pressure on media businesses, at a time when many are still struggling to maintain cash flows. That will subsequently put pressure on the Government to make a deal, and while it’s not certain that this will happen, it seems like there will be an agreement at some stage.

But it’s an interesting case study either way, and it could set a new precedent for Facebook’s negotiations on similar proposals moving forward. Now, other nations know that Facebook will go so far as blocking certain sites if it has to, that its claims are not a bluff. That will mean that anyone looking to push The Social Network will also have to consider the expanded impacts of such shifts.