SOCIAL

New Report Shows Universal Distrust in Social Media as a News Source

The question of misinformation, and its impact on public perception of major issues, has become a key focus in recent times, with social media platforms seen as the main culprit in facilitating the spread of ‘fake news’, leading to confusion and dissent among the populous.

But we don’t know the full impacts of this. For all the study, all the research, for all the data analysis stemming from the 2016 US Presidential Election in particular, it’s impossible to say, for sure, how much impact social media has on people’s opinions – and subsequently, how they vote.

But it must have an impact, right? These days, it feels like we’re more divided along political and ideological lines than ever before, and correlating with that widening gap is the rising use of social platforms, particularly for news content. There must be a connection between the two. Right?

That’s what makes this new study from Pew Research particularly interesting – as per Pew:

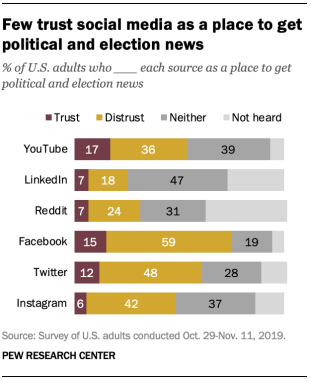

“The current analysis, based on a survey of 12,043 U.S. adults, finds that […] both Democrats and Republicans (including independents who lean toward either party) – in an unusual display of bipartisan convergence – register far more distrust than trust of social media sites as sources for political and election news. And the most distrusted are three giants of the social media landscape – Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.”

In some ways this is both a surprise, and not at the same time. But as you can see, social media platforms – despite now being a more critical news resource for most Americans than print newspapers – are universally not trusted as a source of reliable info.

But social platforms have become a key news pipeline – as noted in another study conducted by Pew in 2018, 68% of Americans now get at least some news content via social media, with 43% getting such from Facebook.

So, despite Facebook now being a leading provider of news content for the majority of people, it’s also the most distrusted news source.

And that does makes sense – there’s a lot of junk floating through Facebook’s network, and as noted, there’s also been a heap of media discussion about political manipulation, Russian interference, etc. But still, with people so distrusting of the info they’re receiving, yet still consuming such at a high rate, it’s little wonder that there’s such confusion and disagreement on the major political issues of the day.

But what’s even more interesting in Pew’s study is that both sides of the political divide distrust social platforms equally, in regards to news content.

So, to recap, more and more people are getting their news info from social media, informing their opinions on the issues of the day. Yet, no one trusts the information they’re reading on social.

So we’re all reading these reports in our News Feeds, and shaking our heads, saying ‘that’s not true’, before realizing that we’re talking to ourselves. And people are looking at us.

Jokes aside, maybe, possibly, this is an example of how social platforms are dividing us. Social algorithm engineers are generally motivated by engagement – if they can show you more content to get you liking and commenting, to get you engaged and active, then the platform, ultimately, wins out. For a long time, a key concern with this approach has been the echo-chamber effect. The algorithms detect what you like, what you’re interested in, based on your on-platform activity, then they show you more, similar content, which keeps you engaged, but may also further solidify one perspective, indoctrinate you into a certain political side, etc.

But what if that’s not the case? If people are universally distrusting of what they’re seeing in their feeds, maybe it’s not the echo chamber effect that we should be worried about, but in fact, the opposite. What if social algorithms actually work to show you more content that you’ll disagree with, in order to spark argument and dissent among users – which, from a functional perspective, is really just engagement and keeping you commenting, sharing, debating, etc.

That would actually align with Facebook’s own findings – in response to the ‘echo chamber’ criticism, Facebook has repeatedly noted that its users are actually shown content from a broader range of sources than non-users, with 26% of the news that users see in their Facebook feeds representing “another point of view”, according to Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg.

But as Facebook exec Andrew Bosworth recently pointed out:

“The focus on filter bubbles causes people to miss the real disaster which is polarization. What happens when you see 26% more content from people you don’t agree with? Does it help you empathize with them as everyone has been suggesting? Nope. It makes you dislike them even more.”

But maybe that’s also the point – if you see more content that you disagree with, that you dislike – that you, indeed, distrust – maybe you’re more inclined to engage with it, as opposed to seeing something that you agree with, then scrolling on through. Maybe, that disagreement and division is central to Facebook’s active engagement, the driving force behind its all-powerful feed algorithm. And maybe, that’s then inciting further polarization, as people are further solidified into one side of the argument or the other in response.

That would explain why all users, on each side of politics, are almost equally distrusting of the news content they see on social, and Facebook in particular. Maybe, then, social media is effectively a hate machine, an anger engine where partisan news wins out, and accurate, balanced journalism is just as easily dismissed.

It certainly doesn’t help that politicians now label reports that they disagree with as ‘fake news’, nor that many media outlets themselves have shifted towards more extreme, divisive coverage in order to boost traffic.

But maybe, that’s what it is. If engagement is your key driver for success, then it’s not agreement that you want to fuel, but the opposite. Disagreement is what gets people talking, what sparks emotional response and fuels debate. It may not be healthy ‘engagement’ as such, but in binary terms – like, say, active engagement rates which you can show to advertisers – it is most definitely ‘engagement’.

Maybe Facebook’s right – it isn’t reinforcing your established beliefs, but challenging them, by making it easier to be angered by those you disagree with.

Think about this – when you go on Facebook, do you more commonly come away feeling happy with the world, or fuming over something that someone has shared?

Maybe, despite echo chambers, misinformation, manipulation, the key divider is our own inherent bias – and Facebook uses this to incite response, which also, invariably, highlights the cracks in society.

Everyone gets news from Facebook, yet no one trusts it. But they might just share it with the comment ‘fake news’, which then flags their political stance, something that their friends and family maybe weren’t aware of previously.

When you consider these results on balance, they actually make a lot more sense than it may, initially, seem.