APPS

The crowd goes wild for Yiming

There’s no shortage of TikTok coverage in the news today as the app’s fate in the U.S. hangs in the air.

What the press doesn’t always address is how TikTok gets here — how did a Chinese startup seize the lucrative short-video market in the West before Google and Facebook? What did it do differently from its Chinese predecessors who tried global expansion to little avail? Matthew Brennan’s new book “Attention Factory” set out to answer these questions by tracing ByteDance’s trajectory from an underdog despised by Chinese tech workers and investors to the envy of Silicon Valley and the target of the White House.

Matthew has spent years working closely with China’s tech firms, not only analyzing them but also using their products as a curious local, experiences that informed his meticulously researched and entertaining book. Interwoven with captivating anecdotes of TikTok, rare photos of ByteDance’s original team, incisive analysis and telling infographics, “Attention Factory” is an essential read for those looking to understand how ideas in the American and Chinese internet worlds collided, coincided and converged throughout the 2010s.

TikTok is a rare example of a Chinese internet service that has gained worldwide success. Before expanding overseas, ByteDance had already proven the short-video model in China through Douyin, the homegrown version of TikTok.

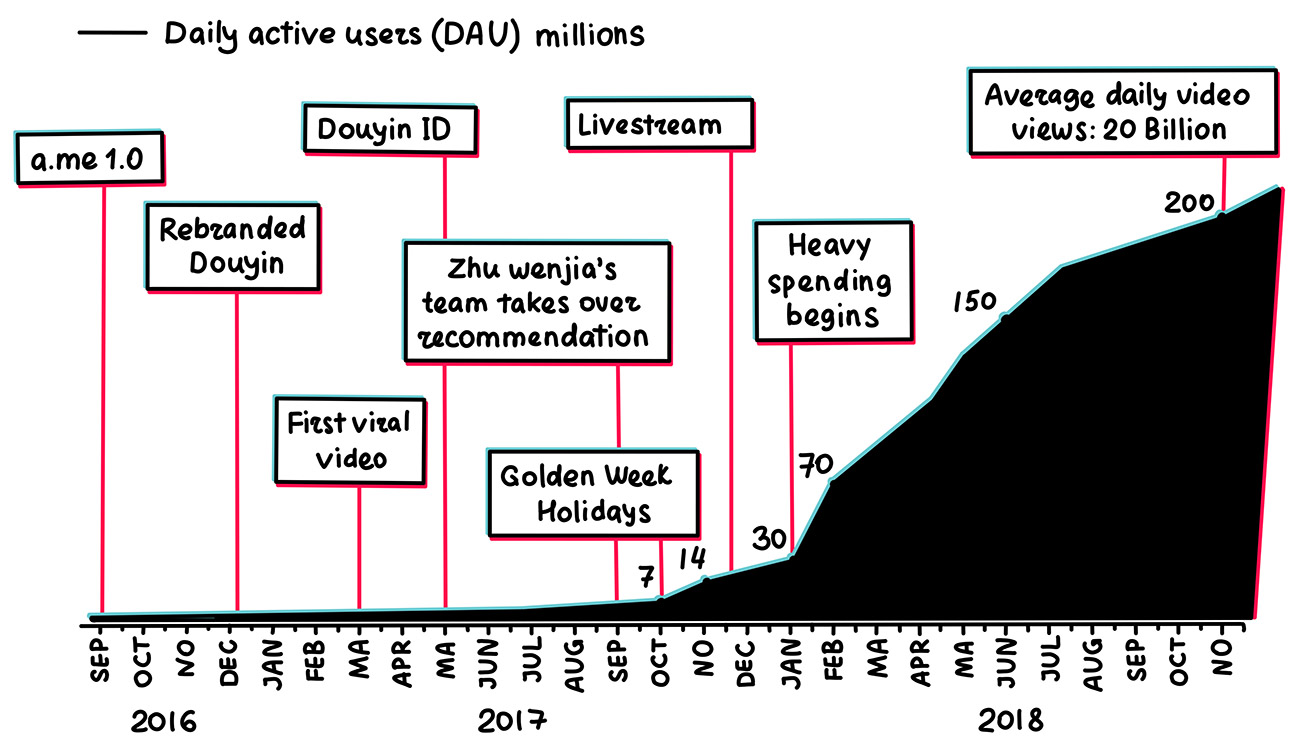

The excerpt below follows a high-growth period of Douyin, detailing how it gained around 200 million daily active users within a year: a loyal creator community, viral memes, algorithmic recommendation and aggressive ad spending.

Before long, the Chinese startup would replicate that growth playbook in the rest of the world, tweaking it here and there to make it work.

Hundreds of fashionably dressed young people were arriving at 751 D.PARK, an expanse of industrial plants redeveloped into a hip culture venue in northeast Beijing. They were clad in baseball caps, brightly colored dresses, loose-fitting hip-hop style streetwear and limited-edition sneakers. The site had been transformed into something akin to the stage of the talent competition “American Idol,” spanning two floors filled with strobe lighting, high-volume music and trendy backdrops. This was an exclusive party — three hundred top Douyin creators coming together to celebrate the app’s one-year anniversary.

The online stars, billed as the “new generation of internet celebrities,” weren’t there to just socialize and enjoy themselves. Every influencer was aware of the unspoken competition to derive the best content from that night. They were all fighting to achieve a higher level of superstardom and the medium of battle was short video.

The influencers who knew each other gathered in small groups as their assistants tirelessly captured fifteen-second videos of their carefully crafted skits. Loners roamed around the dance floor, absorbed in finding the ideal lighting for their lip-syncing selfie videos. Lesser-known influencers nervously approached more famous ones, proposing to record a dance together to potentially tap into their peers’ following. Loud hip-hop music kept playing in the background as creators hurried to touch up the videos they had just shot. Once the editing was done, they uploaded their works and anxiously waited for the app’s algorithms to judge who would grab more eyeballs.

Dance teams took to the stage to display their skills. The crowd bopped their heads back and forth as rappers attempted to impress with clever lyrics. Later as the hosts were midway through giving out awards, a wave of noise erupted from the back of the crowd interrupting the proceedings.

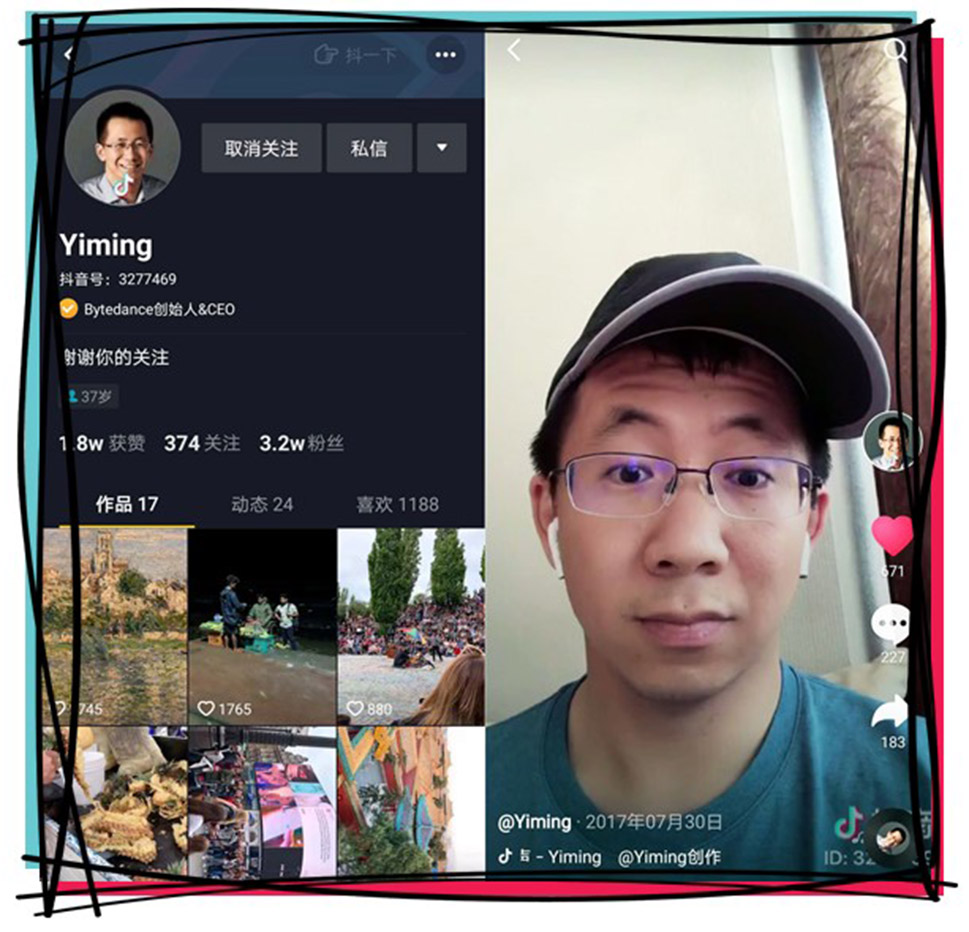

It was Yiming. Dressed in a black baseball cap and gray T-shirt and accompanied by Lidong. The audience went wild — the CEO had decided to drop in unannounced! Immediately he was bombarded with requests to take pictures and videos. As those around him whooped and cried out wildly, the entrepreneur simply smiled and kept his hands calmly by his side, an awkward 34-year-old engineer type among the hyper fashionable, mostly teenage hip-hop crowd.

Yiming and Lidong appear at a Douyin promotional event marking the app’s first anniversary in Sept 2017.

He already knew from looking at the data, but this was confirmation in the flesh — Douyin had built a robust community, with powerful momentum and was on the verge of doing something special.

The breakout

October 1st marks the beginning of “Golden Week,” a seven-day-long official Chinese national holiday. Periods like these are big opportunities for China’s internet industry. People’s behaviors change for a week; many find more time for entertainment and to try new things.

Over October, Douyin’s daily users doubled from seven to 14 million; two months later, they reached 30 million. Over those three months, the 30-day retention rates jumped from eight to over 20%, the average time spent in the app soared from 20 to 40 minutes. It was as if some magic rocket fuel had suddenly been added, boosting every key metric. What had changed?

The answer was Zhu Wenjia. Zhu Wenjia, hired from Baidu in 2015, was widely considered to be one of the top-three best people in the entire company when it came to algorithm technology. He ran one of ByteDance’s most capable engineering teams and had recently been assigned to work on Douyin. The team’s work harnessing the full power of ByteDance’s content recommendation back end led directly to the astounding October results.

The better the metrics, the more resources ByteDance placed behind the app as it now had good retention and was fast-tracked into becoming a strategically important product. Suddenly support was coming in from all over the company — people, money, user traffic, celebrity endorsements, brand collaborations, and most importantly, full integration and optimization of ByteDance’s powerful recommendation engine. Chinese stars with massive fan bases such as Yang Mi, Lu Han, Kris Wu, and Angelababy opened accounts, joining in publicity campaigns, and a nationwide “Douyin Party” event roadshow was planned. Douyin had become the hottest upcoming app in China.

ByteDance ramped up the investment in all three short-video products, including Douyin. People, resources and advertising budget were all raised, leading an industry insider to comment later: “The sudden rise of Douyin wasn’t without good cause. Yiming threw more money at this than anyone and dared to hunt down and grab the best people.”

Commercialization began with the first three brand ad campaigns paid for by Airbnb, Harbin Beer and Chevrolet. Douyin’s advertising business would soon make rapid progress. ByteDance already had hundreds of sales and marketing staff who would shortly be able to add Douyin’s advertisement inventory to their sales targets.

Yiming revealed in a later interview that the company had made it compulsory for everyone on the management team to make their own Douyin videos with goals to gain a certain number of likes or suffer forfeits such as doing push-ups. It wasn’t good enough to just look at charts and data; management needed to understand short videos from a creator’s perspective also. Yiming had watched Douyin videos for a long time but creating his own was “a big step for me,” he admitted.

Yiming’s personal Douyin account (3277469). Seventeen videos at the time of writing, including clips from his global travels.

‘Oh well … karma’s a bitch’

The video opened to a young woman yawning, dressed in pajamas with messy morning hair. Wearing glasses and with no signs of makeup, she casually lip-syncs the line, “Oh well … karma’s a bitch” and throws a silk scarf into the air. Suddenly loud background music explosively begins. In an instant, she transforms into a glamorous fashion model, almost unrecognizable from a second before. A new meme had taken hold of Douyin.

“Karma’s a bitch” was a new version of the original “Don’t judge me” challenge that had propelled Musical.ly to top the U.S. app store three years earlier. The meme was another breakthrough for Douyin; People loved watching the shocking transformations. Compilations of the meme’s videos started popping up online. In particular, the makeup skills of some women left many men in disbelief. “Karma’s a bitch” left an impact on mainstream culture and gained widespread recognition and publicity, even making waves out into English language global media.

Douyin was also increasingly hypercharging the popularity of catchy pop songs with strong hooks. In late 2017, a track known as the “Ci-li-ci-li song” exploded on Douyin. The song’s catchy energy was undeniably infectious. Yet, it was the novel set of dance moves that had become associated with the track’s hook that turned the music into a meme and dramatically amplified its success.

The track had actually been released back in 2013 by Romanian reggae and dancehall artist Matteo, under the name “Panama.” Four years after its debut, the song’s unexpected and explosive spike in popularity led the singer to hastily organize an Asia tour to capitalize on his track’s sudden fame. A YouTube video shows him meeting Chinese fans at the Hangzhou airport who demonstrate their moves to him in the arrivals hall. With the dance having been created entirely in China, the bewildered artist finds himself in the awkward situation of not knowing how to follow the moves to the song for which he is famous.

Perhaps the most reliable indicator of the platform’s increasing influence on society was how the name, Douyin, had started to enter everyday colloquial vernacular, becoming synonymous with short video. The meaning of “Let’s shoot a Douyin!” needed no explanation.

Make it rain

ByteDance knew they now had a winning formula. Retention was good, word of mouth was excellent, a large, vibrant community of video creators had been fostered. The recommendation engine was doing its job of surfacing the best content. Douyin’s fire was already burning bright; now, it was time to pour gasoline on things and spend, spend, spend.

The holiday week of Chinese New Year is another unique annual opportunity for app promotions. Hundreds of millions travel home to be reunited with their families and find themselves with free time to relax. An entertainment app like Douyin was the perfect way to pass the time; word of mouth spread naturally between family members.

To step up its efforts further, Douyin directly gave out money to users by running a Chinese New Year “lucky money” campaign. Users could collect small cash amounts in special videos by tapping on the “red packet” icons — a digital manifestation of cash-filled envelopes people give to each other during the holiday. ByteDance also went all out, spending wildly, buying adverts and promotions across major online channels to acquire users, spending about 4 million yuan a day (over half a million dollars). The combination of all these effects sent Douyin to the top of the Chinese app store charts. Various reports stated Douyin’s daily users jumped from around 40 to 70 million over the February to March period covering Chinese New Year, with some of the top accounts seeing their follower numbers quadruple.

A chart mapping the progress of Douyin, from zero to 200 million daily active users, during the first two years of operation.

This article is an excerpt from “Attention Factory: The Story of TikTok and China’s ByteDance,” which was written by Matthew Brennan and edited by TechCrunch reporter Rita Liao, who wrote the introduction to this post.

TechCrunch