SOCIAL

Virtual Influencers in the Real World | March 2023

Credit: VirtualHumans.org

The next time you buy a flashy new outfit after browsing Instagram, or tap the heart button on a particularly compelling TikTok video, you might discover that the person who posted it isn’t real—and you might not care at all.

That is, if virtual influencers (and their creators) get their way.

A virtual influencer is a digital personality that posts on social media to build an audience of passionate fans, just like a human influencer; at least, that’s how it seems. In reality, a team of humans uses computer-generated imagery (CGI), motion capture, and marketing magic to give a digital avatar a voice, a life, and a brand.

The result makes virtual influencers seem like, well, real people. Just like human influencers, virtual ones share behind-the-scenes posts about their ‘lives’, as well as promoting their favorite products and brands. Virtual influencers usually sound and/or look like humans—or cartoonish representations of them—though they don’t try too hard to hide the fact they are artificial.

Not that audiences seem to care. Top virtual influencers like Lil Miquela, Lu, Noonoouri, and Hatsune Miku have millions of social media followers and routinely post about their lives, feelings, and views. Their followers appear as invested in their lives as they are in the lives of human influencers, if the tens of thousands of likes and comments on virtual influencer posts are any indication.

Virtual influencers even turn digital clout into real-world cash. It’s common for virtual influencers to work hand-in-hand with brands to star in their advertisements and promote their products. At least one has even been signed by a talent agency that usually works with human actors and artists.

Figure. Virtual influencer Miquela Sousa.

“The use of virtual influencers has permeated across many industries, including fashion, beauty, entertainment, and electronics,” says Pierre Benckendorff, a researcher at Australia’s University of Queensland who studies virtual influencers. “And the adoption of virtual influencers is likely to grow in service industries such as tourism and education.”

Virtual influencers are challenging notions of what is possible with technology, and what it means to form relationships online.

In the process, virtual influencers are challenging notions of what is possible with technology — and what it means to form relationships online.

Virtual Influencers, Real-World Impact

Today, virtual influencers are particularly popular in Asia; in China, Japan, and South Korea, they sell products and star in advertisements. Part of their appeal is that they can be adapted to any country or market, says Li Xie-Carson, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Queensland who has researched virtual influencers with Benckendorff.

“Virtual influencers can be tailored for different target markets and cultural tastes. They can be human-like, animal-like, 2D-animated, or 3D-animated,” she says. “This versatility means they can be designed to appeal to audiences in most countries.”

Today’s virtual influencers are not chatbots; they are fully-fledged visual and conversational personas. They sport complete visual bodies and faces, unique personalities, and entire backstories. Behind these influencers are scores of technical and marketing experts who script the influencer’s engagement and create the content that features them in real-world settings.

One of the most famous virtual influencers hailing from the U.S. is known as Lil Miquela. A virtual human who looks like a 19-year-old girl, Lil Miquela posts photos of herself doing everything from eating at restaurants to flying on planes to hanging out with virtual (and real) friends. With almost three million followers on Instagram, each of her posts gets tens of thousands of likes, and hundreds of comments. Through it all, Lil Miquela and her handlers at Brud, the media agency that created her, make no effort to hide the fact she’s not human. (Her Instagram profile says she’s a “19-year-old Robot living in L.A.”)

Fans are not bothered that Lil Miquela is not real; neither are brands. Lil Miquela has become a brand ambassador for luxury brands like Prada and Dior, as well as auto company MINI, promoting their (very real) products to millions of (very real) fans. These partnerships are so lucrative that Lil Miquela has even been signed as talent by Creative Artists Agency (CAA), a major talent agency.

Another major virtual influencer, the Brazil-based Lu do Magalu, often is referred to simply as Lu. While Lil Miquela works with brands, Lu was created by one; she’s the virtual face of Magazine Luiza, a collection of Brazilian companies that includes Magalu, Brazil’s largest retailer. Lu has more than 25 million followers across social media accounts, driven by massive popularity on TikTok. Like any human brand mascot, Lu does her fair share of promoting the company’s products, but she also acts like an actual, approachable person, sharing mundane details about her day, engaging with followers, and even starting conversations around social issues like LGBT rights.

By some counts, hundreds of high-profile virtual influencers exist today, all made possible by a clever mix of advanced technology and human ingenuity.

Other notable virtual influencers act similarly. Noonoouri is a cartoonish virtual influencer who promotes fashion brands worldwide. Hatsune Miku is a popular anime-style virtual influencer who promotes products in the Japanese music industry and performs in virtual concerts. By some counts, hundreds of high-profile virtual influencers exist today, and all of them are made possible by a clever mix of advanced technology and human ingenuity.

From CGI to AI

Virtual influencers like Lil Miquela and Lu are created using the same technologies that make the latest Hollywood blockbusters or mega-hit video games possible.

Explains Benckendorff, three-dimensional (3D) rendering software and motion capture technologies commonly used in gaming and movie productions “are now employed to produce virtual influencers.” That includes tools like MetaHuman, an application from Unreal Engine, a popular graphics engine, that enables users to create photorealistic virtual humans.

Now artificial intelligence (AI) is coming into play to make virtual influencer creation easier, according to Peter Bentley, a professor of computer science at University College London in the U.K. who researches AI. Bentley says highly skilled professionals can use advanced motion capture and CGI to make virtual influencers look hyper-realistic, but deep learning, a sophisticated AI technique, is lowering the level of technical skill needed to produce a real-looking virtual influencer.

“As deep learning methods rapidly mature, we are increasingly able to generate any image we like by replacing existing features with machine learning-generated imagery,” says Bentley. “That makes the process of producing virtual humans even easier, and soon anyone will be able to do this.”

Soon, AI could also change how virtual influencers behave.

Today, most virtual influencers are entirely controlled by humans in graphic design and content development, says Benckendorff; their actions and behaviors are entirely scripted. However, as artificial intelligence continues to grow more powerful, autonomous AI-powered influencers could emerge, with the potential to act on their own to engage with audiences online.

“In the near future, AI influencers may be able to gather user information through natural language processing, image recognition, and speech recognition; create autonomic posts and reply to the audience based on consumer sentiment through problem-solving, and continually improve the interactive process through machine learning,” Benckendorff says.

Deep fakes, in the form of hyper-realistic AI representations of faces, likely also will play a starring role in creating the next generation of virtual influencers. Today, virtual influencers like Lil Miquela and Lu are quite obviously CGI. Tomorrow, with sophisticated AI visuals and behaviors, as well as marketing-savvy human handlers, virtual influencers may be completely indistinguishable from real people, says Zahy Ramadan, a marketing professor at the Lebanese American University in Beirut, Lebanon.

“The virtual lives of virtual influencers are being smartly developed through their omnipresence across social platforms and featuring them next to real people and celebrities,” Ramadan says. “The anthropomorphization is so extreme that many followers [won’t realize] they’re not real.”

Gen Z’s Love Affair with Virtual Influencers

To some, the concept of real humans following virtual influencers might seem ludicrous, but not to certain generations. Generation Z, those born in the late 1990s to the early 2010s, are embracing virtual influencers, says Mona Mrad, a marketing professor at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates. “This generation seems to be well-connected to these influencers, to the extent that they are forming emotional and mental relationships with them,” she says. “They reveal feelings of love and attachment to them.” In some cases, they even perceive virtual influencers to be more reliable than human ones.

These human-virtual influencer bonds are mainly formed on Instagram and TikTok, says Ramadan. The more the virtual influencer is anthropomorphized, he says, the more followers become engaged and emotionally attached to them.

Virtual influencers have already cast their spell on Gen Z, a spell that could grow more powerful if technologies like augmented reality and the metaverse take off. In fact, virtual influencers could become a primary way for us to engage with companies if we spend significant amounts of time in virtual environments, says Sean Sands, a marketing professor at Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology.

“We may all have our own avatar and interact with virtual entities regularly,” Sands says, “so interacting with a service associate that is virtual will seem pretty commonplace.”

Xie-Carson expects interactions between humans and virtual influencers to grow, both online and offline. Even if we don’t spend our lives in the metaverse, virtual influencers have the potential to pop up anywhere we live, work, and shop, thanks to extended reality technology, she says.

“It is possible that technological advances will allow us to get up close and personal with virtual influencers at events, stores, and even schools.”

Further Reading

Further Reading

Hsu, T.,

These Influencers Aren’t Flesh and Blood, Yet Millions Follow Them. The New York Times “June 17, 2019”; http://bit.ly/3W2IFYB

Kuch, T.,

The rise of computer-generated, artificially intelligent influencers. New Scientist “June 8, 2022”; http://bit.ly/3W1tfng

Xie-Carson, L.,

Fake it to Make it: Exploring the use of Virtual Influencers in Tourism. YouTube “Aug. 21, 2022”; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oTR7JI-0QYQ

©2023 ACM 0001-0782/23/03

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and full citation on the first page. Copyright for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers, or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or fee. Request permission to publish from [email protected] or fax (212) 869-0481.

The Digital Library is published by the Association for Computing Machinery. Copyright © 2023 ACM, Inc.

No entries found

SOCIAL

Snapchat Explores New Messaging Retention Feature: A Game-Changer or Risky Move?

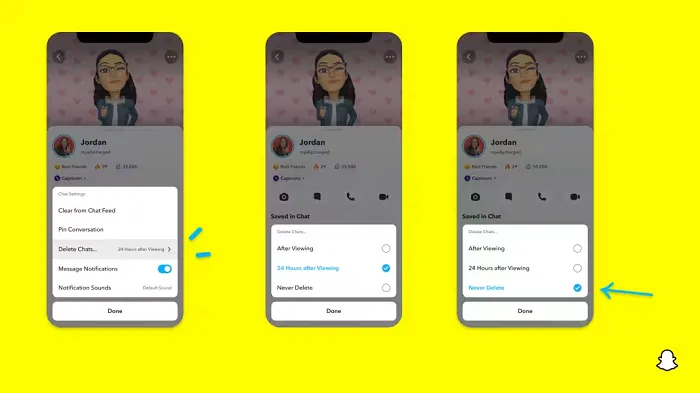

In a recent announcement, Snapchat revealed a groundbreaking update that challenges its traditional design ethos. The platform is experimenting with an option that allows users to defy the 24-hour auto-delete rule, a feature synonymous with Snapchat’s ephemeral messaging model.

The proposed change aims to introduce a “Never delete” option in messaging retention settings, aligning Snapchat more closely with conventional messaging apps. While this move may blur Snapchat’s distinctive selling point, Snap appears convinced of its necessity.

According to Snap, the decision stems from user feedback and a commitment to innovation based on user needs. The company aims to provide greater flexibility and control over conversations, catering to the preferences of its community.

Currently undergoing trials in select markets, the new feature empowers users to adjust retention settings on a conversation-by-conversation basis. Flexibility remains paramount, with participants able to modify settings within chats and receive in-chat notifications to ensure transparency.

Snapchat underscores that the default auto-delete feature will persist, reinforcing its design philosophy centered on ephemerality. However, with the app gaining traction as a primary messaging platform, the option offers users a means to preserve longer chat histories.

The update marks a pivotal moment for Snapchat, renowned for its disappearing message premise, especially popular among younger demographics. Retaining this focus has been pivotal to Snapchat’s identity, but the shift suggests a broader strategy aimed at diversifying its user base.

This strategy may appeal particularly to older demographics, potentially extending Snapchat’s relevance as users age. By emulating features of conventional messaging platforms, Snapchat seeks to enhance its appeal and broaden its reach.

Yet, the introduction of message retention poses questions about Snapchat’s uniqueness. While addressing user demands, the risk of diluting Snapchat’s distinctiveness looms large.

As Snapchat ventures into uncharted territory, the outcome of this experiment remains uncertain. Will message retention propel Snapchat to new heights, or will it compromise the platform’s uniqueness?

Only time will tell.

SOCIAL

Catering to specific audience boosts your business, says accountant turned coach

While it is tempting to try to appeal to a broad audience, the founder of alcohol-free coaching service Just the Tonic, Sandra Parker, believes the best thing you can do for your business is focus on your niche. Here’s how she did just that.

When running a business, reaching out to as many clients as possible can be tempting. But it also risks making your marketing “too generic,” warns Sandra Parker, the founder of Just The Tonic Coaching.

“From the very start of my business, I knew exactly who I could help and who I couldn’t,” Parker told My Biggest Lessons.

Parker struggled with alcohol dependence as a young professional. Today, her business targets high-achieving individuals who face challenges similar to those she had early in her career.

“I understand their frustrations, I understand their fears, and I understand their coping mechanisms and the stories they’re telling themselves,” Parker said. “Because of that, I’m able to market very effectively, to speak in a language that they understand, and am able to reach them.”Â

“I believe that it’s really important that you know exactly who your customer or your client is, and you target them, and you resist the temptation to make your marketing too generic to try and reach everyone,” she explained.

“If you speak specifically to your target clients, you will reach them, and I believe that’s the way that you’re going to be more successful.

Watch the video for more of Sandra Parker’s biggest lessons.

SOCIAL

Instagram Tests Live-Stream Games to Enhance Engagement

Instagram’s testing out some new options to help spice up your live-streams in the app, with some live broadcasters now able to select a game that they can play with viewers in-stream.

As you can see in these example screens, posted by Ahmed Ghanem, some creators now have the option to play either “This or That”, a question and answer prompt that you can share with your viewers, or “Trivia”, to generate more engagement within your IG live-streams.

That could be a simple way to spark more conversation and interaction, which could then lead into further engagement opportunities from your live audience.

Meta’s been exploring more ways to make live-streaming a bigger consideration for IG creators, with a view to live-streams potentially catching on with more users.

That includes the gradual expansion of its “Stars” live-stream donation program, giving more creators in more regions a means to accept donations from live-stream viewers, while back in December, Instagram also added some new options to make it easier to go live using third-party tools via desktop PCs.

Live streaming has been a major shift in China, where shopping live-streams, in particular, have led to massive opportunities for streaming platforms. They haven’t caught on in the same way in Western regions, but as TikTok and YouTube look to push live-stream adoption, there is still a chance that they will become a much bigger element in future.

Which is why IG is also trying to stay in touch, and add more ways for its creators to engage via streams. Live-stream games is another element within this, which could make this a better community-building, and potentially sales-driving option.

We’ve asked Instagram for more information on this test, and we’ll update this post if/when we hear back.

-

SEARCHENGINES6 days ago

Daily Search Forum Recap: April 19, 2024

-

WORDPRESS6 days ago

WORDPRESS6 days ago13 Best HubSpot Alternatives for 2024 (Free + Paid)

-

MARKETING6 days ago

MARKETING6 days agoBattling for Attention in the 2024 Election Year Media Frenzy

-

WORDPRESS6 days ago

WORDPRESS6 days ago7 Best WooCommerce Points and Rewards Plugins (Free & Paid)

-

MARKETING5 days ago

MARKETING5 days agoAdvertising in local markets: A playbook for success

-

SEO6 days ago

SEO6 days agoGoogle Answers Whether Having Two Sites Affects Rankings

-

SEARCHENGINES5 days ago

SEARCHENGINES5 days agoGoogle Core Update Flux, AdSense Ad Intent, California Link Tax & More

-

AFFILIATE MARKETING6 days ago

AFFILIATE MARKETING6 days agoGrab Microsoft Project Professional 2021 for $20 During This Flash Sale

You must be logged in to post a comment Login