SOCIAL

For authors, social media is a powerful tool for self-promotion. It also causes burnout.

Authors can no longer succeed in their craft by writing alone. They must embody multiple roles: writers, publicists, digital marketers, and social media managers. They must be rabid in their self-promotion and steadfast in their personal branding. They have to produce viral tweets, create viral TikTok videos, and optimize their Instagram accounts so that they can get paid to do the work they want to do.

In 2023, writing a book is the easy part.

That’s not to say that self-promotional branding is a novel concept for writers. In the 18th and 19th centuries, authors pulled off some wild stunts to build their brands in newspaper column inches. In the 1920s, Virginia Woolf went shopping with Vogue. Ernest Hemingway did photo ops on safaris and fishing trips. John Steinbeck posed for beer ads. And beyond that kind of classic self-branding, promotion in the 1900s involved a significant amount of personal networking. Anne Sexton, for instance, became a literary star not only because she was an exceptional poet, but also because she was the daughter and wife of salesmen and excellent at self-promotion, as Joy Lanzendorfer pointed out in LitHub. Sexton, who won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1967, tried aggressively to get her work seen. She was ambitious, sending her poems to dozens of publications at a time and hunting down poets she admired, flirting with them, and then demanding they mentor her.

Today, that kind of branding and gumption is still necessary. According to a 2018 study from Paul Ingram of Columbia Business School and Mitali Banerjee of HEC Paris, “artists with a large and diverse network of contacts were most likely to be famous, regardless of how creative their art was.” Now, as our ability to connect with people across the world deepens thanks to social media, writers and artists are held to an even higher standard of networking and connection. This can, of course, be a good thing. In the early 1900s, many people — particularly women, people of color, and those who earn less — weren’t allowed in the same rooms as the successful artists of their day, ensuring their success would be limited by the connections they could make. While racism, sexism, and classism still exist online, social media has burned down some walls.

It has also given authors another requirement for success: virality.

In an era where self-promotion and personal branding reign supreme, authors are under immense pressure to have a social media presence in order to establish themselves as successful writers. And for good reason — BookTok has led to a pretty significant increase in sales for some authors who have gone viral on the platform. But this pressure, while potentially beneficial, can also be a terrible sentence.

Take Nate Lemcke. He wrote a book, Manic Pixie Egirl, and took to social media to promote it. Lemcke decided to read and review a book written by a female author every day until his book made it to the New York Times bestseller list. While attempting to use BookTok to pull in readers isn’t a terrible strategy, he was accused of exploiting the community for his own gain.

“You wrote a book about a self-absorbed man who uses and abuses women. And then, to promote it, you… began to talk about books written by women to appeal to those female readers who control this space,” user @michael.laborn said in a response video. “You are exploiting women. You are using female authors to get you book sales.”

Lemke’s book was being throttled with so many one-star reviews on GoodReads that the platform had to put a hold on reviews altogether. If you searched his name on TikTok, dozens of videos would populate calling him out for his overt sexism and being seemingly uninterested in introspection. He reached virality, which was his goal, even if the reaction was overwhelmingly negative. And, when I spoke to him, he didn’t seem to care.

“If it comes to having to start a gender war on BookTok to sell my book, then [that’s] better than being a waiter until I’m 65,” he told Mashable. “Maybe I’m a sociopath to say that.”

Before the TikTok drama, Lemke had sold fewer than 50 copies of his self-published book. In the month following the drama, he sold 3,000 copies.

Authors feel the push to go viral online — even if it goes terribly and reveals the worst parts about yourself, you’ll still sell more books than if you were silent. Of course, ruining your reputation can hurt your relationship with your publisher, but Lemke’s novel was self-published; he didn’t have much to lose.

Social media platforms offer writers a direct line of communication with their audience, allowing authors to better understand their readers and create a sense of community. In an age where readers often crave personal connections with authors, social media has become a critical tool for building and maintaining these relationships (thanks, John Green).

“Having that social media presence can bring in more fans and get your work noticed more, so there’s always that push to be noticed, to have that hope for that viral moment,” Andrea Stewart, the Sunday Times bestselling author of The Drowning Empire trilogy, told Mashable. “There is some pressure from publishers as well.”

Stewart posts on Instagram, X/Twitter, TikTok, and more platforms just about every day. Her contract didn’t include a social media clause — something that’s become more and more popular among newer writers — but her publisher did send her a social media guide. The guide explains how to post on which social media sites, what kind of content does best on different sites, and when you should post about promotions on Audible or Kindle.

“There’s nothing that they say directly that says you have to be on social media, but the fact is that it is expected,” Stewart said. “It’s this unspoken rule.”

Victoria Aveyard, the New York Times bestselling author of the Red Queen series, also doesn’t have a social media clause in her contract. Still, she posts on Instagram, TikTok, and X/Twitter daily — on top of being on deadline for her newest book.

“I do understand the need, and the benefit [of posting on social media], but it can be extremely overwhelming for an author,” Aveyard told Mashable over email. “Especially debuts, who realize upon selling a book that writing the manuscript was only half the job. Now we have to help sell it! And most of us have no idea how to do that, or where to even start.”

Some authors have language in their contracts that requires them to post and promote their work weekly on Instagram, X/Twitter, and TikTok. These kinds of social media clauses change depending on who the writer, agent, and publisher are, and not everyone has one. However, the requirement to be online adds a great deal of work for the writers. It’s not that social media equates to book sales in a one-to-one ratio. Because, as Stewart says, there just is a limited amount of real-time data.

“We don’t know when we make a post on social media whether or not that’s moving the needle or it’s something that the publisher is doing marketing-wise,” Stewart said. “There’s that vagueness, so you feel like you have to do it because you want to do everything to make your book succeed. That’s part of the package.”

And, as Aveyard said, despite the lack of data, “a good social media presence helps me sell books. It helps my backlist and my frontlist. It helps new readers find my old books and old readers find my new ones.”

However, posting so frequently takes away from writing. Creating videos and posts every single day takes time and creativity — both of which are necessary for writing and can feel limited. You can batch content, sure, but ultimately there’s an aspect of social media that requires you to be online, responding to comments in real-time.

“[Social media] is one million percent a distraction, and I find I have less time to write as I maintain an active social media presence,” Aveyard said. “Maybe I should have a social media manager or someone to help me edit content, but currently it’s just me, and I hope that helps my platforms feel genuine. I tell myself it’s all in service of the job and keeping my books front of mind for readers. Sometimes that’s true. Sometimes it’s bullshit.”

The metrics-driven nature of social media can also be disheartening for authors. The pursuit of likes, shares, and followers can sometimes overshadow the true essence of writing — the love for storytelling and the desire to connect with readers on a deeper level. Authors may feel disappointed if their posts do not receive the expected engagement, leading to self-doubt and a sense of inadequacy.

But it’s not all bad. Posting on social media can help authors foster relationships and create communities online with other people who fully understand their struggles.

“I want to keep writing forever and to do that in traditional publishing, I need to keep selling,” Aveyard said. “It’s time-consuming, it’s stressful, but it also gives me some illusion of control in a profession in which I have very little. And frankly, I do enjoy a lot of social media and making content. It helps me connect to my readers, understand what they connect to in my work, and just feel like I’m not alone in my work. If I didn’t enjoy it, I don’t think I would have the audience I do now.”

SOCIAL

12 Proven Methods to Make Money Blogging in 2024

This is a contributed article.

This is a contributed article.

The world of blogging continues to thrive in 2024, offering a compelling avenue for creative minds to share their knowledge, build an audience, and even turn their passion into profit. Whether you’re a seasoned blogger or just starting, there are numerous effective strategies to monetize your blog and achieve financial success. Here, we delve into 12 proven methods to make money blogging in 2024:

1. Embrace Niche Expertise:

Standing out in the vast blogosphere requires focus. Carving a niche allows you to cater to a specific audience with targeted content. This not only builds a loyal following but also positions you as an authority in your chosen field. Whether it’s gardening techniques, travel hacking tips, or the intricacies of cryptocurrency, delve deep into a subject you’re passionate and knowledgeable about. Targeted audiences are more receptive to monetization efforts, making them ideal for success.

2. Content is King (and Queen):

High-quality content remains the cornerstone of any successful blog. In 2024, readers crave informative, engaging, and well-written content that solves their problems, answers their questions, or entertains them. Invest time in crafting valuable blog posts, articles, or videos that resonate with your target audience.

- Focus on evergreen content: Create content that remains relevant for a long time, attracting consistent traffic and boosting your earning potential.

- Incorporate multimedia: Spice up your content with captivating images, infographics, or even videos to enhance reader engagement and improve SEO.

- Maintain consistency: Develop a regular publishing schedule to build anticipation and keep your audience coming back for more.

3. The Power of SEO:

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) ensures your blog ranks high in search engine results for relevant keywords. This increases organic traffic, the lifeblood of any monetization strategy.

- Keyword research: Use keyword research tools to identify terms your target audience searches for. Strategically incorporate these keywords into your content naturally.

- Technical SEO: Optimize your blog’s loading speed, mobile responsiveness, and overall technical aspects to improve search engine ranking.

- Backlink building: Encourage other websites to link back to your content, boosting your blog’s authority in the eyes of search engines.

4. Monetization Magic: Affiliate Marketing

Affiliate marketing allows you to earn commissions by promoting other companies’ products or services. When a reader clicks on your affiliate link and makes a purchase, you get a commission.

- Choose relevant affiliates: Promote products or services that align with your niche and resonate with your audience.

- Transparency is key: Disclose your affiliate relationships clearly to your readers and build trust.

- Integrate strategically: Don’t just bombard readers with links. Weave affiliate promotions naturally into your content, highlighting the value proposition.

5. Display Advertising: A Classic Approach

Display advertising involves placing banner ads, text ads, or other visual elements on your blog. When a reader clicks on an ad, you earn revenue.

- Choose reputable ad networks: Partner with established ad networks that offer competitive rates and relevant ads for your audience.

- Strategic ad placement: Place ads thoughtfully, avoiding an overwhelming experience for readers.

- Track your performance: Monitor ad clicks and conversions to measure the effectiveness of your ad placements and optimize for better results.

6. Offer Premium Content:

Providing exclusive, in-depth content behind a paywall can generate additional income. This could be premium blog posts, ebooks, online courses, or webinars.

- Deliver exceptional value: Ensure your premium content offers significant value that justifies the price tag.

- Multiple pricing options: Consider offering tiered subscription plans to cater to different audience needs and budgets.

- Promote effectively: Highlight the benefits of your premium content and encourage readers to subscribe.

7. Coaching and Consulting:

Leverage your expertise by offering coaching or consulting services related to your niche. Readers who find your content valuable may be interested in personalized guidance.

- Position yourself as an expert: Showcase your qualifications, experience, and client testimonials to build trust and establish your credibility.

- Offer free consultations: Provide a limited free consultation to potential clients, allowing them to experience your expertise firsthand.

- Develop clear packages: Outline different coaching or consulting packages with varying time commitments and pricing structures.

8. The Power of Community: Online Events and Webinars

Host online events or webinars related to your niche. These events offer valuable content while also providing an opportunity to promote other monetization avenues.

- Interactive and engaging: Structure your online events to be interactive with polls, Q&A sessions, or live chats. Click here to learn more about image marketing with Q&A sessions and live chats.

9. Embrace the Power of Email Marketing:

Building an email list allows you to foster stronger relationships with your audience and promote your content and offerings directly.

- Offer valuable incentives: Encourage readers to subscribe by offering exclusive content, discounts, or early access to new products.

- Segmentation is key: Segment your email list based on reader interests to send targeted campaigns that resonate more effectively.

- Regular communication: Maintain consistent communication with your subscribers through engaging newsletters or updates.

10. Sell Your Own Products:

Take your expertise to the next level by creating and selling your own products. This could be physical merchandise, digital downloads, or even printables related to your niche.

- Identify audience needs: Develop products that address the specific needs and desires of your target audience.

- High-quality offerings: Invest in creating high-quality products that offer exceptional value and user experience.

- Utilize multiple platforms: Sell your products through your blog, online marketplaces, or even social media platforms.

11. Sponsorships and Brand Collaborations:

Partner with brands or businesses relevant to your niche for sponsored content or collaborations. This can be a lucrative way to leverage your audience and generate income.

- Maintain editorial control: While working with sponsors, ensure you retain editorial control to maintain your blog’s authenticity and audience trust.

- Disclosures are essential: Clearly disclose sponsored content to readers, upholding transparency and ethical practices.

- Align with your niche: Partner with brands that complement your content and resonate with your audience.

12. Freelancing and Paid Writing Opportunities:

Your blog can serve as a springboard for freelance writing opportunities. Showcase your writing skills and expertise through your blog content, attracting potential clients.

- Target relevant publications: Identify online publications, websites, or magazines related to your niche and pitch your writing services.

- High-quality samples: Include high-quality blog posts from your site as writing samples when pitching to potential clients.

- Develop strong writing skills: Continuously hone your writing skills and stay updated on current trends in your niche to deliver exceptional work.

Conclusion:

Building a successful blog that generates income requires dedication, strategic planning, and high-quality content. In today’s digital age, there are numerous opportunities to make money online through blogging. By utilizing a combination of methods such as affiliate marketing, sponsored content, and selling digital products or services, you can leverage your blog’s potential and achieve financial success.

Remember, consistency in posting, engaging with your audience, and staying adaptable to trends are key to thriving in the ever-evolving blogosphere. Embrace new strategies, refine your approaches, and always keep your readers at the forefront of your content creation journey. With dedication and the right approach, your blog has the potential to become a valuable source of income and a platform for sharing your knowledge and passion with the world, making money online while doing what you love.

Image Credit: DepositPhotos

SOCIAL

Snapchat Explores New Messaging Retention Feature: A Game-Changer or Risky Move?

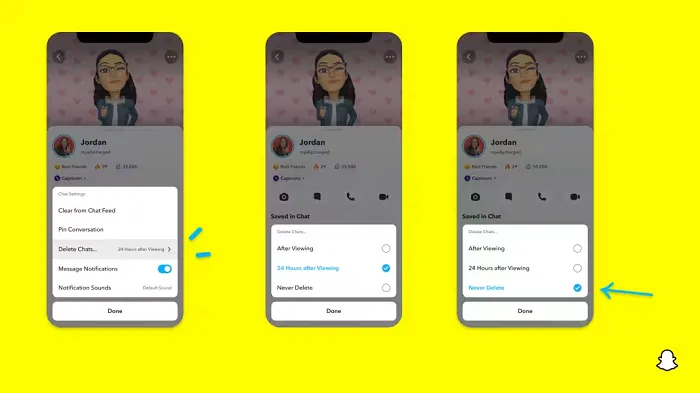

In a recent announcement, Snapchat revealed a groundbreaking update that challenges its traditional design ethos. The platform is experimenting with an option that allows users to defy the 24-hour auto-delete rule, a feature synonymous with Snapchat’s ephemeral messaging model.

The proposed change aims to introduce a “Never delete” option in messaging retention settings, aligning Snapchat more closely with conventional messaging apps. While this move may blur Snapchat’s distinctive selling point, Snap appears convinced of its necessity.

According to Snap, the decision stems from user feedback and a commitment to innovation based on user needs. The company aims to provide greater flexibility and control over conversations, catering to the preferences of its community.

Currently undergoing trials in select markets, the new feature empowers users to adjust retention settings on a conversation-by-conversation basis. Flexibility remains paramount, with participants able to modify settings within chats and receive in-chat notifications to ensure transparency.

Snapchat underscores that the default auto-delete feature will persist, reinforcing its design philosophy centered on ephemerality. However, with the app gaining traction as a primary messaging platform, the option offers users a means to preserve longer chat histories.

The update marks a pivotal moment for Snapchat, renowned for its disappearing message premise, especially popular among younger demographics. Retaining this focus has been pivotal to Snapchat’s identity, but the shift suggests a broader strategy aimed at diversifying its user base.

This strategy may appeal particularly to older demographics, potentially extending Snapchat’s relevance as users age. By emulating features of conventional messaging platforms, Snapchat seeks to enhance its appeal and broaden its reach.

Yet, the introduction of message retention poses questions about Snapchat’s uniqueness. While addressing user demands, the risk of diluting Snapchat’s distinctiveness looms large.

As Snapchat ventures into uncharted territory, the outcome of this experiment remains uncertain. Will message retention propel Snapchat to new heights, or will it compromise the platform’s uniqueness?

Only time will tell.

SOCIAL

Catering to specific audience boosts your business, says accountant turned coach

While it is tempting to try to appeal to a broad audience, the founder of alcohol-free coaching service Just the Tonic, Sandra Parker, believes the best thing you can do for your business is focus on your niche. Here’s how she did just that.

When running a business, reaching out to as many clients as possible can be tempting. But it also risks making your marketing “too generic,” warns Sandra Parker, the founder of Just The Tonic Coaching.

“From the very start of my business, I knew exactly who I could help and who I couldn’t,” Parker told My Biggest Lessons.

Parker struggled with alcohol dependence as a young professional. Today, her business targets high-achieving individuals who face challenges similar to those she had early in her career.

“I understand their frustrations, I understand their fears, and I understand their coping mechanisms and the stories they’re telling themselves,” Parker said. “Because of that, I’m able to market very effectively, to speak in a language that they understand, and am able to reach them.”Â

“I believe that it’s really important that you know exactly who your customer or your client is, and you target them, and you resist the temptation to make your marketing too generic to try and reach everyone,” she explained.

“If you speak specifically to your target clients, you will reach them, and I believe that’s the way that you’re going to be more successful.

Watch the video for more of Sandra Parker’s biggest lessons.

-

MARKETING3 days ago

MARKETING3 days ago18 Events and Conferences for Black Entrepreneurs in 2024

-

MARKETING5 days ago

MARKETING5 days agoAdvertising on Hulu: Ad Formats, Examples & Tips

-

WORDPRESS5 days ago

WORDPRESS5 days agoBest WordPress Plugins of All Time: Updated List for 2024

-

MARKETING6 days ago

MARKETING6 days agoUpdates to data build service for better developer experiences

-

WORDPRESS6 days ago

WORDPRESS6 days agoShopify Could Be Undervalued Based On A Long-Term Horizon

-

PPC6 days ago

PPC6 days agoLow Risk, High Reward YouTube Ads alexking

-

WORDPRESS4 days ago

WORDPRESS4 days ago5 Must See Telegram Plugins for WooCommerce

-

MARKETING3 days ago

MARKETING3 days agoIAB Podcast Upfront highlights rebounding audiences and increased innovation