MARKETING

The Optimizely Podcast – episode 26: digital evolution in a climate of rapid change

Transcript:

Laura Dolan:

Hello everyone. And welcome to the Optimizely Podcast. I am Laura Dolan, your host, and today we are joined by Dom Graveson, who’s the director of strategy and experience at Netcel and Deane Barker, who is the global director of content management here at Optimizely. How’s it going, gentlemen?

Dom Graveson:

Yeah, very good, thank you. How are you?

Laura Dolan:

Doing well, doing well. How about you Deane? How’s it going?

Deane Barker:

Good, Laura. I’m a veteran of this podcast by now.

Laura Dolan:

You are. You are, Deane. So we already know all about you. So Dom, please, let’s start off by telling us a little bit about your background and your history of Netcel.

Dom Graveson:

Yeah, sure. So I’ve been with Netcel for coming up for four years. Netcel are a digital product and experience development company, so we build everything from kind of websites through to integration with CRM, marcoms, basically building digital experiences on the Optimizely platform.

Dom Graveson:

We do a lot of work with kind of experience research and data, so we kind of put customers at the center of all the work we do, but also, we understand that there’s quite a profound impact on businesses. So when you are really going to deliver transformational digital experiences and really up your digital game, particularly in the current climate and the world that everything’s changed so much recently, you are going to need to change your organization and the way that you govern, the way that you manage people, so we do a lot of work with our clients, kind of helping them through that process as well, the kind of change process.

Dom Graveson:

Previous to that, I was with some of the big sort of consultancies working on digital product innovation. I worked around all over the world. So yeah, I kind of bring a few years of experience and broad experience to this.

Laura Dolan:

Very good. Can you speak on some of the digital experience that you’ve worked on with Optimizely?

Dom Graveson:

Yeah, so we’ve built products, digital experiences for some of the major not-for-profit organizations in the U.K. So we mainly work in the U.K., U.K. Based, based just North of London. We’re working currently with a large agricultural organization that represents Britain’s farmers around building kind of digital experiences and business-to-business commerce systems with them. So, yeah, then we also work with quite a lot of well-known financial services businesses in the U.K. As well. So our kind of focus has been membership organizations, business-to-business, and financial services with bits of NFP, not-for-profit, as well.

Laura Dolan:

Very cool. Thank you so much for spending a little bit of time on that. I always like to know our relationship with partners, so it’s nice to have that visibility. So today we are talking about the digital evolution in a climate of very rapid change. So what do we mean by digital evolution as opposed to the more traditional concept of digital transformation?

Dom Graveson:

Well, I mean, it’s been something I think that’s been emerging for a while, but for the last kind of 15 years or so, or 20 years since digital really kind of took hold as it were and became a kind of serious channel that organizations were taken seriously, it always seemed that the focus was on getting from A to B or getting from where we are now to a level of competence and capability, which we can define at the beginning of the project.

Dom Graveson:

And I think over the last few years, or over that time really, we’ve seen that become less and less of an appropriate or working approach. And what we are trying to encourage now, and what we are building within the businesses that we work with is this approach to digital, which is more of an evolution rather than the transformation. Because if you’re working across a three-year program, what you define as being the destination now, certainly in the last few years, probably isn’t going to be relevant or fit for purpose within three years of you delivering it, and a lot of IT and digital projects fail to meet their objectives because of this exact approach.

Dom Graveson:

So it’s about kind of structuring your programs in a way that keeps an open mind, a beginner’s mind, and has the instruments within it, and governance within it, and structure that will enable you to discover as you go and focus on outcomes or customer outcomes, business outcomes, rather than thinking too much about kind of architecting the house before you start building, when you don’t know where you’re building it yet, if that makes sense.

Laura Dolan:

Absolutely. Deane, is there anything you can contribute to this as well?

Deane Barker:

So Dom and I did an event together in London at the very top of The Gherkin and we had a long conversation up there. We had a panel discussion up there. We had a long conversation about the fact that digital transformation is maybe a term that we need to retire, replace it with digital evolution, or digital progress, or digital incrementalism. And it’s just the general idea that you make your way over time. You make little bets, and you improve your digital estate piece by piece. I think that too many people are doing too much at one time and digital projects are failing for that reason, whereas they’re not being more deliberate about their goals and they’re not giving themselves room to evolve organically, make one step and see where that leads them, and then make another step and see where that leads them. And I think the goal of instant complete transformational overhaul is maybe unrealistic for a lot of digital teams. So that was the conversation that Dom and I had, which kind of led us the idea of digital evolution. So that’s kind of the perspective we’re coming on.

Dom Graveson:

Yeah. I think also what’s interesting with that is the idea that as Deane was saying that if you’re doing more than one thing at once and something works, how do you know which thing made it work, gave you the success? And one of the things that people aren’t investing in, they’re investing heavily in kind of a sense, trying to make progress, but not investing very heavily in measuring that progress or actually understanding and interpreting that data to be able to understand what was the thing that they did that delivered that benefit. And this is one of the aspects where we need to change the way that we work. It’s interesting, we’ve kind of heard of a major project just this week, big program in the U.K. That’s really struggling. I won’t mention names, but it’s really struggling because they’ve been so desperate to achieve a certain point that they’ve kind of lost their way.

Dom Graveson:

They’ve hired lots of people. They’ve got lots of people leading different parts of the product and all the rest of it, but they kind of lost their way because in their quest to arrive somewhere so quickly or make progress, they’ve kind of lost track of where they were trying to get from the business objectives’ point of view. And I think that’s a common problem. I mean, I’ve been in this business 25 years, I guess, and something I see again and again, that if we can build the team to a certain size or if we can get this kind of throughput of features shipped, we will arrive somewhere.

Dom Graveson:

And of course, that’s important. Progress is at the heart of all of this. But you do need to keep this mindset, as Deane mentioned, this kind of incrementalist mindset, of break things down, take it a step at a time, and structure the organization, manage upward, manage your sponsors robustly so that they understand that this is not something that you can just steamroller into existence. It’s much more of a kind of step forward across a series of fronts to make progress. And that takes kind of courage and communication with all kinds of levels of the organization.

Laura Dolan:

It does. And it is a very common problem because you end up with too many cooks in the kitchen as it were, and then you also end up with a quantity over quality issue, which is such a common problem that you find within organizations. And then you also have the issue of just all the siloing that goes on and the lack of transparency between different departments, and so you have this huge team, but they’re not communicating with each other. So that’s also just a very difficult thing to work around and there has to be a better way, don’t you think?

Dom Graveson:

Yeah. I mean think this is the thing, is that this is why people need to want… Where I’ve seen this successful is where it’s seen as an organizational change, as much as it’s seen as a program of delivery of product or delivery of an experience or new channels or whatever, is that the organization needs to learn and change as the program evolves. You can’t just throw tons of money at this. You need to understand how it’s going to require people to behave differently, work together differently, measure things differently, check in on one another, enable mistakes to be made in a way that people aren’t afraid of that, and that they get surfaced quickly, and that they’re maturely and honestly addressed, all that kind of stuff. And I think a lot of some kind of wasted money over the last 10, 15 years has been where that hasn’t really been seen.

Dom Graveson:

The business case has been made for the program, for the objectives of the program, without really thinking about how the organization is going to change. And organizations are changing, have changed profoundly in the last few years. We’re working from home. We’ve changed the way that we interact with one another socially. We’ve got political upheaval in the U.S. We’ve got a war in Europe. We’ve got all of this stuff that’s really changed the way that we kind of feel about the world and trust is more important than ever and kind of empathy, and understanding, and individualized experiences, and all of these things are not just technical problems to solve by throwing a load of infrastructure in place.

Dom Graveson:

Infrastructure is important, but it’s also about building an experimental mindset. It’s about empowering your people to take risks in a safe environment. It’s about changing the way that your organizations have run right from the top to show and demonstrate that behavior is understood from the frontline all the way to the C-suite.

Laura Dolan:

Hundred percent. So when you talk about these changes that organizations need to make to dovetail into this evolution, where have you seen this approach be successful? Do you have any examples that you can describe for us?

Dom Graveson:

Yeah. When I think where we’ve talked about it, and Deane feel free to jump in here, is where I’ve seen it on organizations of all kinds of sizes that have invested in their digital teams, both from the kind of point of view of giving them the freedom to be able to innovate and the freedom to be able to try new things out, try new technologies out, and build experiences, and invest in audience research, and kind of pulling together the kind of insights, departments and sources of insight within the organization, but also where they’ve had the visibility and had the visible support from the senior leadership.

Dom Graveson:

I think still, you see quite a lot of digital teams being run by either technology or marketing. And I think digital is something that is actually the responsibility of the whole business now, the whole organization. I don’t know, Deane, have you got any thoughts on this? We talked about it extendedly.

Deane Barker:

You and I have talked about this, Dom, and I think I’ve talked about this in the podcast before, is that a key component of digital leadership is trust. Do you trust your people to work towards the good of the organization. Too often, we get kind of hampered by the tyranny of metrics. We need an instant uplift. We need an instant improvement, where that really discourages your team from making small changes and running experiments and trying new things that might not work. For some reason, we want everybody to guarantee that everything’s going to work right out of the box. It’s not. And I think if you trust your teams and provide them kind of the emotional and professional safety to make small changes, and see what works, and come back to you and say, “Look, we tried five things. Four of them didn’t work, but this one thing worked really, really well.”

Deane Barker:

I’m big on taking little bets, small incremental changes, and lengthening the periods required for return and results. If you demand quantitative metric results from your team in 30 days, you’re going to get some very brittle results, if anything. Someone might even be massaging some numbers or framing it in such a way to give you the numbers that you want. But if you sit your team down and say, “Look, I’d like to be in a better place this time next year.” Well then, they can come up with a long term plan, and they can try some things and see what works and see what doesn’t work, and I also think that plays very heavily into employee retention. I think that lets your employees do their best work and be satisfied with their job and satisfied with their efforts, and I think it’s a huge win for the organization, but it takes trust. As a leader, you need to believe that your people are skilled and are working towards the benefit of the organization, and some leaders are more shortsighted than others, let’s say.

Dom Graveson:

It’s interesting, actually. You talk about this kind of leaders wanting results quickly because I think that’s a reality of organizations on this part is. And one of the things that I think a lot of kind of chief digital officers who we tend to work with are struggling between… I have this kind of analogy I use, which is a bit like you’re running a chip van. You’re trying to feed people, hot dogs and chips in the rain and there’s a big queue of people and everyone’s hungry, and you know that you could evolve your product and make better food, but you’re so bogged down by having to kind of feed people that you never get the chance to think about that. And I think one of the things that we talk about is building this idea of a balanced portfolio.

Dom Graveson:

So digital evolution or digital transformation, but digital evolution is always going to be kind of made up of combination of small little bits of quick win work and big core transformational change, which are things like integrating your CRM, or migrating your digital experience platform, or swapping out your ERP or whatever. And you’ve always got this combination of the quick wins, the things that if you’re going to bring the business on the journey with you, you need to demonstrate some simple improvements, such as the marketing team in South America just can’t update their campaigns without calling you. And of course, you are running a chip van, so they’re going to be 15th in the queue, so they’re furious. They don’t want to hear about your big innovation program of new digital experience with the customer centricity. They just want to update their campaigns. So it’s about balancing a number of simple things that you can do for everybody, along with those longer term transformational changes.

Dom Graveson:

And then a third part, which is what we call future possible, which is looking at what technology or platforms might be useful in the future for you and experimenting. So you’ve got this, do the simple stuff that just the CEO, she’s just getting hassled for every day from her colleagues. Get our stuff fixed, because that’ll make you popular and it’ll build you some support. Obviously investing in the, not being afraid to make decisions that are long term. This is not the right platform. We need to change, or we need to integrate this with this, or we need to invest in these people and up-skill them. That’s the kind of big kind of transformational stuff. And then these experiments that will help you discover what the future is. And you have to govern each of those three types of portfolios in a different way, and understand that the experiments will fail, most of them. But that’s where you will discover that the pot of gold for five years’ time, whereas the quick win or BAU, I hate that term BAU, but the quick win stuff, which is really important in building support.

Laura Dolan:

So how can organizations get started on the digital evolution journey?

Deane Barker:

Well, I’ve always been a big proponent of absolutely knowing what your goals are, what your conversion points, are for your digital presence. A conversion, most people know this now, but a conversion is when somebody takes an action in your digital properties that provides value. Ecommerce, it’s somebody checks out or in other websites, if somebody requests a demo or something like that, you have to know what these things are. You have to know the moment that your visitor provides value and the moment that your digital presence has provided value to you. Without knowing that you’re just nowhere, and we see a lot of people doing an enormous amount of work without any idea kind of what the goal is.

Deane Barker:

Back when I was in services, I was working with a healthcare client, and I was talking to their director of marketing. He says, the CEO calls me all the time and says, “We need more social media updates.” And he would go back to the CEO and say, “Why?” And the CEO couldn’t even tell them why, because the CEO didn’t understand the chain from action that the digital team takes to conversion or some moment when the website provides value. So you have to know that. Once you know that, the conversion points when your website provides them value, then you just need to break things down. You need to divide your web presence up into chunks that you can improve over time. Too many people just try to tackle the entire thing at once.

Deane Barker:

Let’s take a look at your contact dose form. Maybe we need to spend some time just fixing that. And then, let’s move to your homepage and run a couple experiments there. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that Optimizely sells an experimentation suite. Run a couple experiments on your homepage. What’s it going to take to drive people to that contact form? Literally, if that’s the goal that you know have to improve, you can work towards improving that goal and you can filter out people in the organization that have pet projects, or pet ideas, or they’re sure that this is going to make things better. If you can go back to them and say, “Nope, this is the goal. This is the goal we’re working towards,” you can start making incremental steps toward improving that goal. And that’s probably the most important thing that an organization can do.

Dom Graveson:

Yeah. I mean think Deane hits upon two things that are really interesting there. The first one is a lot of people that we work with or often one of the struggles that heads of digital have is, I keep getting asked to do kind of crazy things like create more social media posts by senior people, which adds to that whole noise, that adds to the queue of the backlog of urgent stuff that needs doing, that means that you never get the chance to stop and actually think about things strategically.

Dom Graveson:

And actually, there’s an element of a lack of understanding within very senior people because maybe they’re not so experienced at working within the kind of digital space. Although to be honest, it’s been 20 years. I have little sympathy for that now. An organization that’s probably not only just digital first, but pretty much digital all over. If you think about it now, your first interaction with an organization is going to be probably through its digital channels, and maybe even the entire service experience will be through digital channels. Leaders should get this by now, right?

Dom Graveson:

But my point is that if digital teams are getting kind of requests from leadership, such as create loads of social media posts or build us an app is another one I’ve heard. “We need an app.” “Well, why do we need an app?” Is because actually there’s a responsibility on digital leaders to step up and be leaders and to be able to say, “Right. You need to tell us where this business needs to be. And we will help develop an understanding of what those key conversion points are.” You can’t expect senior, necessarily people who aren’t sort of native digital folk to understand that. But if you provide them with that information, I hope you would get less of those kinds of slightly daft requests. If you see what I mean, Deane, I think there’s a responsibility on digital professionals to educate upwards. And rather than kind of feel like if you’re in an organization that’s struggling, change that organization if you can. It’s a two-way thing.

Deane Barker:

This goes back to trust, right?

Dom Graveson:

Yeah.

Deane Barker:

The reason why you have people in digital, not resisting calls to do things that aren’t going to provide value is because professional insecurity. They don’t believe that their leaders trust them. They think they just have to do whatever the CEO or the CMO tells them to do. They don’t feel like they can push back. I have been working in the digital space for 25 years and everything comes back to organizational and personal psychology at some level. I think you have people in digital team that they just don’t feel like they can push back and make the right suggestions. And they just have to do what someone higher at the [inaudible 00:22:13] tells them to do, and that’s just a recipe for disaster, really.

Dom Graveson:

It also means you’re going to lose the other best people you have, because no one with any integrity and real talent will stick around if that’s the kind of corporate environment that they’re in. People have a lot of choice these days, particularly with increasing mobility and hybrid working, is that really the world is your talent market now and you can find the best people if you build the best cultures, and it doesn’t really matter where they live. For example, Netcel, some of us live outside of the U.K., Some of us live across the U.K., And it’s worked very well.

Dom Graveson:

But I think this thing about what Deane was saying about breaking it down and we touched upon this in the answer to the last question about the balance portfolio. This is where you do need to break down those conversion points and how we improve those conversion points into a really simple set of steps, that by improving this, you can understand how you are influencing the outcome. So don’t necessarily need to rebuild the whole of your shopping funnel, for example, or your conversion funnel, but build a program and invest in this experimentation.

Dom Graveson:

So, this is both in the platform, as Deane said, Optimizely has an experimentation suite built into it, but also working with the agency, the partner that you work with, to understand how experimentation works. At Netcel, we do a lot of work with pitch leaders on kind of building out both kind of capability at the kind of operational level. How do I design an experiment, but also about how you build a business case for experimentation, and kind of build a business case for broader digital evolution as a concept. We’ve actually published a report that you can download from Netcel.com/report that talks a lot about this, that’s Deane’s been involved with and some other leading digital professionals as well. So, if you wanted to read more, you can check that out. That’s been supported by Optimizely. Yeah, so there’s some good sort of starting points in that.

Laura Dolan:

Yes, please go ahead and send me that link when you can, Dom, and I will definitely put it in the link to the show notes of this podcast that we will have on our website. Perfect. Thank you. Great. You guys have covered a lot and just being conscious of time, is there anything else that we didn’t cover that you’d like to speak on before we wrap up?

Deane Barker:

Both Dom and I have alluded to the concept of employee morale, psychology and retention. And I think this is one of the big crises in digital right now, is that people are searching for the organization that gets it. People are searching for the organization that they can work at, and feel good about their work, and feel like they’re making a positive impact. And so when you hamper your digital teams, when you try to overload them, when you are vague with them, and you don’t have clear goals with them, you don’t let them try new things and incrementally make improvements, you hurt your organization in two ways.

Deane Barker:

Number one, just through lack of conversion, right? Lack of digital efficiency and effectiveness, but you also hurt them from lack employee morale and retention. Losing digital employees is so painful because they’re so painful to replace these days. And so, the damage to your organization is considerable and I think it’s very shortsighted to put some 30-day quantitative metric in front of that.

Dom Graveson:

Yeah. I mean, I completely agree with that, and I think one of the ways that you can tackle that is by ensuring that you’ve got… Digital isn’t something that’s just done with the digital team or just done by the digital team. We talk a lot about digital operating models with the clients that we work with, and this is where we get into the kind of, how do you govern and lead digital, not just how do you build the right products, or build the right experiences.

Dom Graveson:

But if, for example, you’re a professional services company and you want to segment to different markets and build authority in different markets, say you’re a lawyer firm or another kind of professional services firm. You want to build authority in merchants and acquisitions. You want to build authority in sports licensing law. You are going to need a lot of help from the people in your organization to generate that content. That content isn’t going to be generated necessarily by the digital team. But the digital team are there as an enabler. They’re there to provide the technology and the advice and the kind of lead and give people the confidence to be able to create content themselves, to be able to create their own campaigns.

Dom Graveson:

So digital is something that actually another principle and concept that Deane and I have been talking about recently is this idea of digital is like water. It’s kind of everywhere and you don’t notice it, as if you’re a fish, and we’ll put the link to that article in the podcast as well. There’s this idea that actually everyone should be responsible for doing digital to a level of excellence across your organization in the same way that everyone’s able to write emails to a level of excellence across the organization. And your digital teams are really there to set the standard, set examples, measure success, share that success, build a center of excellence, but also enable everyone else. So, you don’t need to necessarily overwork people. You can give people the tools they need to be able to run their own operations and the digital elements of their operations, but with the oversight and support from the digital team. So, this is known as a kind of hub and spoke model.

Dom Graveson:

And this has been a really powerful way of scaling digital, where you don’t want to overload your digital teams. The digital leaders can stay being exactly that, leaders, innovators, consultants, working within the organization to set the agenda, to build the infrastructure that your organization needs for the future, while training up and building basic levels of high-quality digital competencies in your marketing teams, in your customer service teams, in your product development teams, in all the different parts of your organization that interface with customers. And that’s been a really successful model for many, and I think I’m one that has a kind of rosy future ahead of it.

Laura Dolan:

I love that you brought up the, “What is water?” paper. I had a chance to read that and it’s a very interesting article and I know Deane, you actually sent a YouTube video that talks about the commencement speech. So, I am also going to put a link to that in the article, because it is quite fascinating and quite applicable as I said. So, thank you both for contributing both of those pieces that would supplement this subject that we talked about today. I think that’ll really drive the point home.

Deane Barker:

Dom and I have a shared love of David Foster Wallace.

Dom Graveson:

Yes, indeed.

Laura Dolan:

Awesome. Well, thank you both so much for taking the time to come on today and thank you all so much for taking the time to listen to this episode of the Optimizely Podcast. I am Laura Dolan, and I will see you next time.

Laura Dolan:

Thank you for listening to this edition of the Optimizely Podcast. If you’d like to check out more episodes or learn more about how we can take your business to the next level by using our marketing, content, or experimentation tools, please visit our website at optimizely.com, or you can contact us directly using the link at the bottom of this podcast blog to hear more about how our products will help you unlock your digital potential.

MARKETING

IAB Podcast Upfront highlights rebounding audiences and increased innovation

Podcasts are bouncing back from last year’s slowdown with digital audio publishers, tech partners and brands innovating to build deep relationships with listeners.

At the IAB Podcast Upfront in New York this week, hit shows and successful brand placements were lauded. In addition to the excitement generated by stars like Jon Stewart and Charlamagne tha God, the numbers gauging the industry also showed promise.

U.S. podcast revenue is expected to grow 12% to reach $2 billion — up from 5% growth last year — according to a new IAB/PwC study. Podcasts are projected to reach $2.6 billion by 2026.

The growth is fueled by engaging content and the ability to measure its impact. Adtech is stepping in to measure, prove return on spend and manage brand safety in gripping, sometimes contentious, environments.

“As audio continues to evolve and gain traction, you can expect to hear new innovations around data, measurement, attribution and, crucially, about the ability to assess podcasting’s contribution to KPIs in comparison to other channels in the media mix,” said IAB CEO David Cohen, in his opening remarks.

Comedy and sports leading the way

Podcasting’s slowed growth in 2023 was indicative of lower ad budgets overall as advertisers braced for economic headwinds, according to Matt Shapo, director, Media Center for IAB, in his keynote. The drought is largely over. Data from media analytics firm Guideline found podcast gross media spend up 21.7% in Q1 2024 over Q1 2023. Monthly U.S. podcast listeners now number 135 million, averaging 8.3 podcast episodes per week, according to Edison Research.

Comedy overtook sports and news to become the top podcast category, according to the new IAB report, “U.S. Podcast Advertising Revenue Study: 2023 Revenue & 2024-2026 Growth Projects.” Comedy podcasts gained nearly 300 new advertisers in Q4 2023.

Sports defended second place among popular genres in the report. Announcements from the stage largely followed these preferences.

Jon Stewart, who recently returned to “The Daily Show” to host Mondays, announced a new podcast, “The Weekly Show with Jon Stewart,” via video message at the Upfront. The podcast will start next month and is part of Paramount Audio’s roster, which has a strong sports lineup thanks to its association with CBS Sports.

Reaching underserved groups and tastes

IHeartMedia toasted its partnership with radio and TV host Charlamagne tha God. Charlamagne’s The Black Effect is the largest podcast network in the U.S. for and by black creators. Comedian Jess Hilarious spoke about becoming the newest co-host of the long-running “The Breakfast Club” earlier this year, and doing it while pregnant.

The company also announced a new partnership with Hello Sunshine, a media company founded by Oscar-winner Reese Witherspoon. One resulting podcast, “The Bright Side,” is hosted by journalists Danielle Robay and Simone Boyce. The inspiration for the show was to tell positive stories as a counterweight to negativity in the culture.

With such a large population listening to podcasts, advertisers can now benefit from reaching specific groups catered to by fine-tuned creators and topics. As the top U.S. audio network, iHeartMedia touted its reach of 276 million broadcast listeners.

Connecting advertisers with the right audience

Through its acquisition of technology, including audio adtech company Triton Digital in 2021, as well as data partnerships, iHeartMedia claims a targetable audience of 34 million podcast listeners through its podcast network, and a broader audio audience of 226 million for advertisers, using first- and third-party data.

“A more diverse audience is tuning in, creating more opportunities for more genres to reach consumers — from true crime to business to history to science and culture, there is content for everyone,” Cohen said.

The IAB study found that the top individual advertiser categories in 2023 were Arts, Entertainment and Media (14%), Financial Services (13%), CPG (12%) and Retail (11%). The largest segment of advertisers was Other (27%), which means many podcast advertisers have distinct products and services and are looking to connect with similarly personalized content.

Acast, the top global podcast network, founded in Stockholm a decade ago, boasts 125,000 shows and 400 million monthly listeners. The company acquired podcast database Podchaser in 2022 to gain insights on 4.5 million podcasts (at the time) with over 1.7 billion data points.

Measurement and brand safety

Technology is catching up to the sheer volume of content in the digital audio space. Measurement company Adelaide developed its standard unit of attention, the AU, to predict how effective ad placements will be in an “apples to apples” way across channels. This method is used by The Coca-Cola Company, NBA and AB InBev, among other big advertisers.

In a study with National Public Media, which includes NPR radio and popular podcasts like the “Tiny Desk” concert series, Adelaide found that NPR, on average, scored 10% higher than Adelaide’s Podcast AU Benchmarks, correlating to full-funnel outcomes. NPR listeners weren’t just clicking through to advertisers’ sites, they were considering making a purchase.

Advertisers can also get deep insights on ad effectiveness through Wondery’s premium podcasts — the company was acquired by Amazon in 2020. Ads on its podcasts can now be managed through the Amazon DSP, and measurement of purchases resulting from ads will soon be available.

The podcast landscape is growing rapidly, and advertisers are understandably concerned about involving their brands with potentially controversial content. AI company Seekr develops large language models (LLMs) to analyze online content, including the context around what’s being said on a podcast. It offers a civility rating that determines if a podcast mentioning “shootings,” for instance, is speaking responsibly and civilly about the topic. In doing so, Seekr adds a layer of confidence for advertisers who would otherwise pass over an opportunity to reach an engaged audience on a topic that means a lot to them. Seekr recently partnered with ad agency Oxford Road to bring more confidence to clients.

“When we move beyond the top 100 podcasts, it becomes infinitely more challenging for these long tails of podcasts to be discovered and monetized,” said Pat LaCroix, EVP, strategic partnerships at Seekr. “Media has a trust problem. We’re living in a time of content fragmentation, political polarization and misinformation. This is all leading to a complex and challenging environment for brands to navigate, especially in a channel where brand safety tools have been in the infancy stage.”

Dig deeper: 10 top marketing podcasts for 2024

MARKETING

Foundations of Agency Success: Simplifying Operations for Growth

Why do we read books like Traction, Scaling Up, and the E-Myth and still struggle with implementing systems, defining processes, and training people in our agency?

Those are incredibly comprehensive methodologies. And yet digital agencies still suffer from feast or famine months, inconsistent results and timelines on projects, quality control, revisions, and much more. It’s not because they aren’t excellent at what they do. I

t’s not because there isn’t value in their service. It’s often because they haven’t defined the three most important elements of delivery: the how, the when, and the why.

Complicating our operations early on can lead to a ton of failure in implementing them. Business owners overcomplicate their own processes, hesitate to write things down, and then there’s a ton of operational drag in the company.

Couple that with split attention and paper-thin resources and you have yourself an agency that spends most of its time putting out fires, reacting to problems with clients, and generally building a culture of “the Founder/Creative Director/Leader will fix it” mentality.

Before we chat through how truly simple this can all be, let’s first go back to the beginning.

When we start our companies, we’re told to hustle. And hustle hard. We’re coached that it takes a ton of effort to create momentum, close deals, hire people, and manage projects. And that is all true. There is a ton of work that goes into getting a business up and running.

The challenge is that we all adopt this habit of burning the candle at both ends and the middle all for the sake of growing the business. And we bring that habit into the next stage of growth when our business needs… you guessed it… exactly the opposite.

In Mike Michalowitz’s book, Profit First he opens by insisting the reader understand and accept a fundamental truth: our business is a cash-eating monster. The truth is, our business is also a time-eating monster. And it’s only when we realize that as long as we keep feeding it our time and our resources, it’ll gobble everything up leaving you with nothing in your pocket and a ton of confusion around why you can’t grow.

Truth is, financial problems are easy compared to operational problems. Money is everywhere. You can go get a loan or go create more revenue by providing value easily. What’s harder is taking that money and creating systems that produce profitably. Next level is taking that money, creating profit and time freedom.

In my bestselling book, The Sabbatical Method, I teach owners how to fundamentally peel back the time they spend in their company, doing everything, and how it can save owners a lot of money, time, and headaches by professionalizing their operations.

The tough part about being a digital agency owner is that you likely started your business because you were great at something. Building websites, creating Search Engine Optimization strategies, or running paid media campaigns. And then you ended up running a company. Those are two very different things.

How to Get Out of Your Own Way and Create Some Simple Structure for Your Agency…

- Start Working Less

I know this sounds really brash and counterintuitive, but I’ve seen it work wonders for clients and colleagues alike. I often say you can’t see the label from inside the bottle and I’ve found no truer statement when it comes to things like planning, vision, direction, and operations creation.

Owners who stay in the weeds of their business while trying to build the structure are like hunters in the jungle hacking through the brush with a machete, getting nowhere with really sore arms. Instead, define your work day, create those boundaries of involvement, stop working weekends, nights and jumping over people’s heads to solve problems.

It’ll help you get another vantage point on your company and your team can build some autonomy in the meantime.

- Master the Art of Knowledge Transfer

There are two ways to impart knowledge on others: apprenticeship and writing something down. Apprenticeship began as a lifelong relationship and often knowledge was only retained by ONE person who would carry on your method.

Writing things down used to be limited (before the printing press) to whoever held the pages.

We’re fortunate that today, we have many ways of imparting knowledge to our team. And creating this habit early on can save a business from being dependent on any one person who has a bunch of “how” and “when” up in their noggin.

While you’re taking some time to get out of the day-to-day, start writing things down and recording your screen (use a tool like loom.com) while you’re answering questions.

Deposit those teachings into a company knowledge base, a central location for company resources. Some of the most scaleable and sellable companies I’ve ever worked with had this habit down pat.

- Define Your Processes

Lean in. No fancy tool or software is going to save your company. Every team I’ve ever worked with who came to me with a half-built project management tool suffered immensely from not first defining their process. This isn’t easy to do, but it can be simple.

The thing that hangs up most teams to dry is simply making decisions. If you can decide how you do something, when you do it and why it’s happening that way, you’ve already won. I know exactly what you’re thinking: our process changes all the time, per client, per engagement, etc. That’s fine.

Small businesses should be finding better, more efficient ways to do things all the time. Developing your processes and creating a maintenance effort to keep them accurate and updated is going to be a liferaft in choppy seas. You’ll be able to cling to it when the agency gets busy.

“I’m so busy, how can I possibly work less and make time for this?”

You can’t afford not to do this work. Burning the candle at both ends and the middle will catch up eventually and in some form or another. Whether it’s burnout, clients churning out of the company, a team member leaving, some huge, unexpected tax bill.

I’ve heard all the stories and they all suck. It’s easier than ever to start a business and it’s harder than ever to keep one. This work might not be sexy, but it gives us the freedom we craved when we began our companies.

Start small and simple and watch your company become more predictable and your team more efficient.

MARKETING

Advertising on Hulu: Ad Formats, Examples & Tips

With the continued rise in streaming service adoption, advertisers are increasingly turning to OTT (over-the-top) advertising, which allows brands to reach their target audiences while they stream television shows and movies. OTT advertising is advertising delivered directly to viewers over the internet through streaming services or devices, such as streaming sticks and connected TVs. One of the most popular streaming ad-supported streaming services today is Hulu.

At just $7.99 per month (with ads) and $17.99 per month (without ads), Hulu is a great deal. And where the deals are incredible, the subscribers follow…

The formula itself is one we’re all familiar with, and it appears to be working out quite well for Hulu.

- Low prices attract more viewers

- More viewers brings more eyes to Hulu ads

- More eyes on ads brings more interested advertisers

- Advertising revenue climbs alongside impressive viewer growth

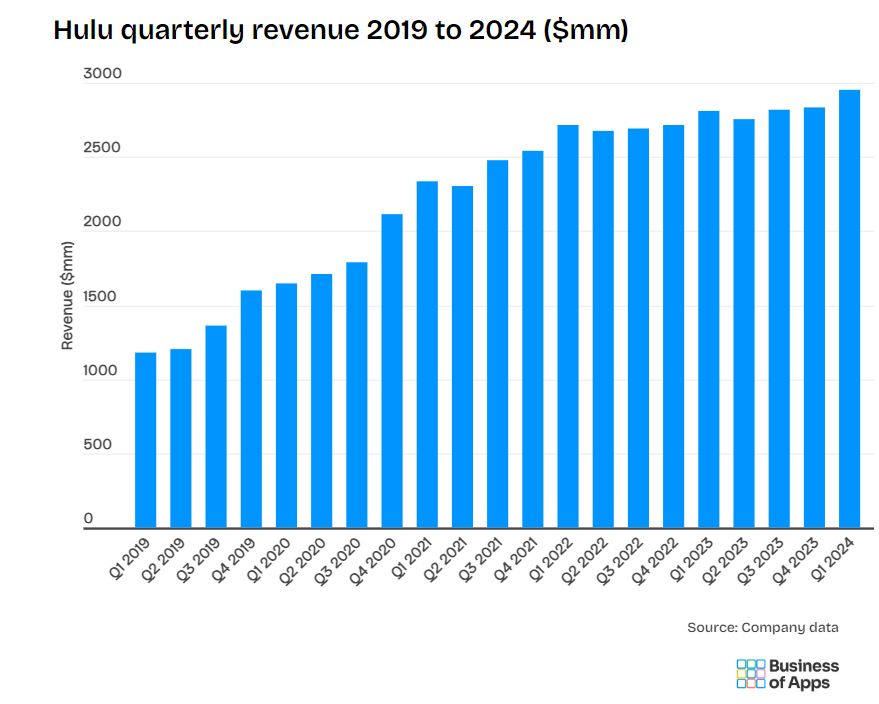

In this particular scenario, everyone wins! And the proof is in the pudding considering Hulu generated $11.2 billion in revenue in 2023.

In the following article, we will cover everything you need to know about Hulu including how to advertise on Hulu, ad types available, advertising cost, best examples of Hulu ads, and more. Let’s dive right in.

What is Hulu Advertising?

Image Source: https://www.emarketer.com/content/disney-will-become-streaming-heavyweight

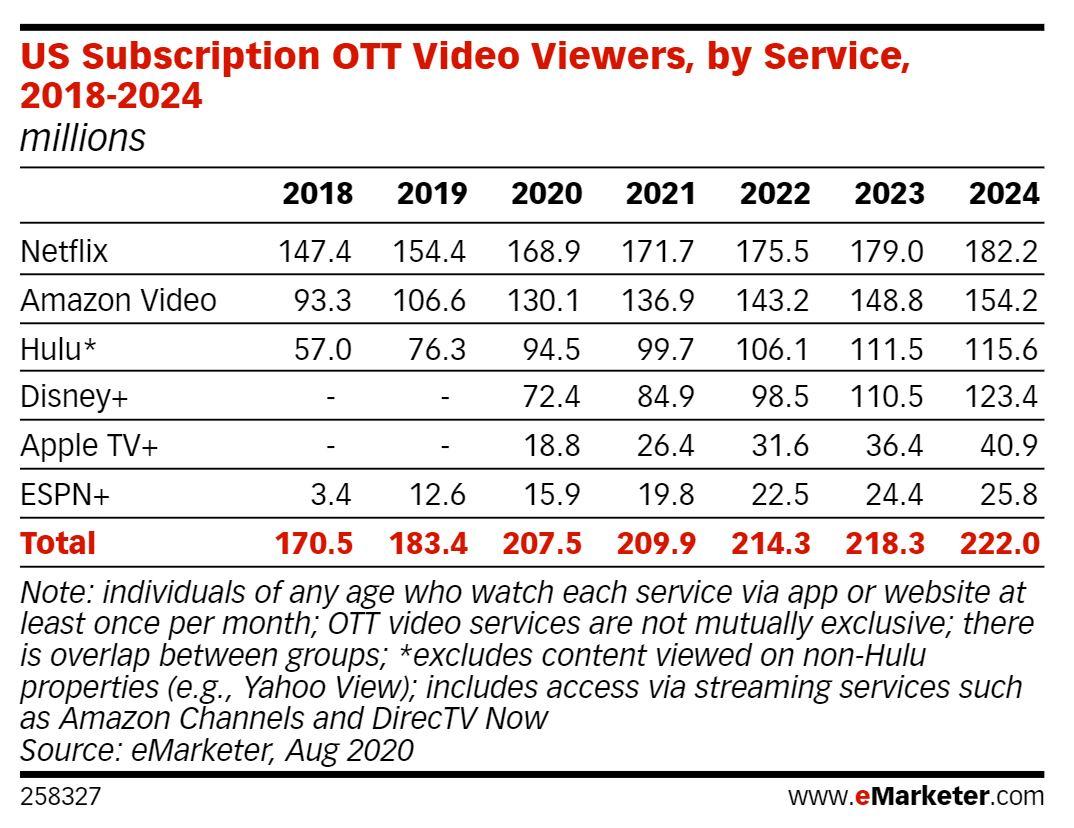

Hulu is a service that offers subscription video on demand. Hulu currently has more than 50.2 million subscribers across their SVOD (ad-free subscription video on demand) and AVOD (advertising-based video on demand) plans, translating to nearly 100 million viewers in 2021. eMarketer predictions estimate that number will grow to 115.6 million viewers by 2024.

Hulu notes on their website that their ad-supported offering is their most popular. Previously shared statistics showed that in 2023, 58% of total Hulu subscribers opted for the ad-supported plan.

Hulu subscriptions can be purchased on their own, or as part of a bundle with other services. One such popular option is The Disney Bundle. The new Disney Bundle brings together the extensive Disney+ and Hulu libraries – including beloved characters, award-winning films and series, and 100 years’ worth of inspiring stories – all in one place.

Hulu’s ad-supported and ad-free plans offer subscribers a vast streaming library, inclusive of thousands of movies and TV episodes. Hulu Originals are also included in both plans, as is the ability to watch on the internet-enabled device of your choosing—TV, mobile, tablet, or laptop. As the first platform to introduce viewer-first advertising innovations, like the industry’s first interactive ad formats, Hulu continues to give viewers choice and control over their ad experience.

Outside of the primary differentiators between the two options—ads or no ads, and cost—the only additional distinction to be made is that the ad-supported version does not allow subscribers to download and watch titles on-the-go.

Hulu offers a popular option with an ad-supported tier. This utilizes OTT advertising, meaning ads are delivered directly to viewers over the internet through the Hulu platform, rather than traditional cable or satellite TV. Unlike a typical TV buy where you get a set amount of ad space, these OTT ad buys allow for granular targeting based on demographics, location, and interests, similar to what you might experience on other digital platforms. While these ads are strategically placed before, during, and potentially after your chosen content, they are not skippable. It’s also worth noting that even ad-free tiers might show a few promotional spots for certain shows or live TV events.

Hulu has its very own ad platform that includes a robust set of options for bidding, targeting, and measurement, as well as different ad experiences.

Why Advertise on Hulu?

In today’s media landscape, reaching your target audience effectively is crucial. Hulu offers a compelling advertising platform with a variety of advantages:

- Massive Reach – Tap into a vast audience of engaged viewers. Hulu boasts over 50.2 million subscribers, with their AVOD tier reaching a staggering 109.2 million viewers per month.

- Targeted Engagement – Go beyond traditional TV’s limitations. Hulu’s targeting capabilities allow you to zero in on specific demographics, interests, and even geographies. This ensures your message reaches viewers most likely to resonate with your brand.

- Cost-Effectiveness – Hulu has many buy options, which makes it accessible for any size client to run a campaign on Hulu. Hulu offers campaign minimums as low as $500, which creates a low barrier to entry for most clients. Especially, when partnering with an agency like Tinuiti, where brands can anticipate 2-3x more efficient CPMs when compared to the general market. This makes it accessible for businesses of various sizes to test and refine their advertising strategies.

- DRAX – Disney’s Real-Time Ad Exchange establishes direct connections to major media buying platforms for streamlined ad buying across Disney+ and Hulu. This integration increases automation, allowing advertisers easier access to Disney’s inventory. Partnerships with Google and The Trade Desk provide direct paths to Disney’s inventory, offering greater reach, flexibility, and transparency.

- Engaging Ad Formats – Hulu offers a variety of ad formats beyond standard video ads. Explore interactive elements to capture viewer attention and create a more immersive brand experience with Shoppable ads, pause ads, takeovers, and more.

- Brand Safety – Hulu prioritizes brand safety, ensuring your ads appear alongside high-quality content. This minimizes the risk of your brand being associated with inappropriate content.

By leveraging Hulu’s advertising solutions, you can target engaged viewers, deliver impactful messaging, and ultimately reach your marketing goals.

How Advertising on Hulu Works

Hulu offers brands of all sizes a chance to advertise on their platform. And since Hulu falls under the Disney umbrella, advertising opportunities extend beyond the Hulu platform itself. There are opportunities to buy into inventory cross ESPN, Disney+, ABC and more.

It’s important to keep in mind, the method through which you purchase ads plays a role in the measurement insights you’ll receive. Below are the three primary ways to buy ad placements on Hulu, with additional details regarding programmatic buys, and Hulu’s self-service platform.

- Purchase ads directly from Hulu sales teams

- Programmatic ad buys

- Through Hulu’s self-service platform (currently invite-only, but brands can request access)

If you’re not ready to pick up the phone and collaborate with Hulu’s sales team on a large ad buy, you’re probably going to end up using Programmatic Guaranteed ad buys or purchase ad space through the Self Service Platform. Here’s a little more information on each option:

Programmatic Guaranteed (Reserved Buys) and Private Marketplace (Auctionable)

Ads purchased through a programmatic sales team that works directly with platforms and streaming agencies, like Tinuiti. This offers advanced local and national targeting and measurement capabilities, enhanced reporting, and suite of targeting options at fixed or biddable rates.

Whether you want to target lookalike audiences, specific demographics, interest or behavioral segments, or leverage audience CRM matching for a customized group, you’ll know exactly when and where your ads showed, and be provided with robust reporting that helps measure what’s working best, and where you should continue to invest for optimal performance. You’ll also enjoy guaranteed media buys that ensure you get the expected visibility and reach.

There are certain Hulu ad types that can’t be purchased programmatically, including sponsored placements, pause ads, and ad-selector ads, among other standout units. For these types, Tinuiti makes reserved buys for our clients from opportunities that are only available through Hulu directly.

Not sure which ad types make the most sense for your business and advertising goals? Our team works with clients to determine which campaign initiatives are best for them, and help ensure their creative meets Hulu’s requirements.

Self-Service Hulu Ads (Beta) – Must RSVP and Be Approved as a Brand

Hulu’s self-serve ad platform allows brands to access ad inventory directly, with a modest $500 campaign minimum. These ads are ideal for smaller businesses that don’t have a sizable streaming ads budget, or are just getting started with OTT and want to test the waters.

The Self-Service Ads beta program offers a glimpse into the future of advertising on Hulu. With features like budget management, targeted audience selection, and ad format flexibility (to some extent), businesses can craft impactful campaigns tailored to their specific needs. However, remember the current limitations and the need for approval before getting started.

Reporting Limitations: Notably, when purchasing through the self-service platform, your reporting will only include impression data; you won’t have insights into where your ads actually ran.

While this offering is still in beta, Hulu has already shared some early success stories. Learn more here about how Hulu self-serve ads work.

How Much Does Hulu Advertising Cost?

Unlike traditional ad buys, Hulu advertising utilizes a cost-per-thousand-impressions (CPM) model. This means you pay each time one thousand viewers see your ad, with estimates ranging from $10 to $30 CPM. Factors like targeting specifics, competition, and ad format (pre-roll vs. mid-roll, length) can influence the final cost.

Hulu advertising costs are structured to allow for advertisers of all sizes and budgets, but the total costs, you’ll realize, will largely depend on a number of factors, including:

- Whether you’re buying directly through Hulu or a DSP (demand-side platform)

- Any restrictions you place on Hulu regarding where your ads display. Specific audience or genre targeting, and/or frequency caps, may incur a premium as well

- Which ad types you choose

- How much creative you will need to generate for your ads (production costs)

- Seasonality—Q4 advertising costs are higher than other quarters

- Whether you’re buying through an up-front agreement (advertising commitment for a full TV season), or the scatter market (ad buys that run month-to-month, or quarter-to-quarter)

How to Advertise on Hulu

Here’s what you need to know to advertise on Hulu, from buying and targeting to measurement and optimization.

Hulu offers several advertising reach options for brands:

- National: Reach viewers across the US

- Local: Reach a localized target audience

- Advanced TV: Automated, data-informed ad buys

Within the Advanced TV category, Hulu has 3 different bidding options:

- Programmatic Guaranteed: Automated, guaranteed buy with advanced targeting.

- Private Marketplace: Non-guaranteed buy with increased targeting control.

- Invite-Only Auction: Find your audience, set your price, and optimize from within your DSP

In Hulu’s invite-only auction, advertisers select their target audience, determine their bid price for that audience, and control and optimize their ad campaigns in real-time based on results and performance. You can learn more about Hulu’s advanced targeting options here.

When it comes to executing Hulu ads, at Tinuiti, we can take on all the heavy lifting for you.

Ad Types Available on Hulu [With Specs]

In today’s streaming world, capturing viewers’ attention is more important than ever. When it comes to Hulu ads, pre-roll placements (those shown before your chosen content) are proven to be highly effective, especially earlier slots within the pre-roll sequence. This is prime real estate for grabbing viewers before they settle into their show.

But don’t be limited! Hulu offers a variety of ad formats to suit your needs, including pre-roll, mid-roll (shown during commercial breaks within the content), and even 7-second bumper ads for quick, impactful messaging. Whether you choose a short and sweet 7-second spot or a more detailed 15 or 30-second video ad, Hulu offers the flexibility to tailor your message to your audience and campaign goals.

When creating your Hulu video ad, it’s important to follow their specifications including:

- Video Duration: 15 to 30 seconds

- Audio Duration: Must match video duration

- Dimensions: 1920×1080 preferred; 1280×720 accepted

- Display Aspect Ratios: 16:9 preferred; Hulu will accept videos shot with 2.39:1, 1.375:1, 3:4, or 4:3 dimensions, but you must make the video fit a 16:9 ratio by inserting matting on the top and bottom of the video.

- Video Format: QuickTime, MOV, or MPEG-4

- File Extensions: .mov or .mp4

- File Size: 10 GB maximum

- Audio Format: PCM, AAC

- Frame Rate: 23.98, 24, 25, 29.97, or 30 fps

- Frame Rate Mode: Constant

- Video Bit Depth: 8 or 16 bits

- Video Bit Rate: 10 Mbps – 40 Mbps

- Audio Bit Depth: 16 or 24 bits (for audio channel 2)

- Audio Bit Rate: 192-256

- Chroma Subsampling: 4:2:0 or 4:2:2

- Codec ID: Apple ProRes 422 HQ preferred; H.264 accepted

- Color Space: YUV

- Scan Type: Progressive Scan

- Audio Channels: 2 channel stereo

- Audio Sampling Rate: 48.0 kHz

Hulu offers what they call “a viewer-first ad experience” made up of an extensive variety of different ad products and solutions, including:

Video Commercial

This is the most ‘standard’ ad type available from Hulu, with your video playing during any “long-form content commercial breaks.” Hulu allows 7-, 15- and 30-second video commercials, and “does not accept stitched Ads.” This simply means that if advertisers want to display a 30-second commercial, they will be required to have an asset of the correct length, and can’t ‘stitch together’ two separate 15-second ads.

Ad Selector

This ad type gives the viewer greater control over their ad experience. Viewers will be given the option to choose between two or three different video ads to watch from the same advertiser. This can increase the chances that viewers will be engaged with your ad as they had some degree of choice in watching it. If no ad selection is made within 15 seconds of being presented with the options, one of the two or three available ads will be selected at random and played automatically.

According to Hulu Brand Lift Norms, 2020, products like these that “give viewers choice and control” have “result[ed] in 70% higher lifts than the average campaign on Hulu.”

Branded Entertainment Selector (BES)

Choice comes into play with Hulu’s BES ads as well, but in this scenario, they are choosing not just their ad experience, but their viewing experience as well. Viewers are given the option to watch their programming of choice with the typical commercial breaks, or to enjoy their programming uninterrupted by first watching a longer ad. We like to think of it as finishing your dinner before eating dessert! This is a popular choice for advertisers who want to tell a story with their ad—or advertise a movie or upcoming event—and need more than 15 or 30 seconds to do so.

Binge Ad

Want to reach viewers dedicating some of their downtime to an hours-long binge session, but don’t want to risk hitting them with the same ad, delivered in the same way, episode after episode? Hulu’s Binge Ad placements are designed with brand safety and a positive watching experience in mind. These “enable marketers to deliver contextually and situationally-relevant messages at the right time and place – during a viewer’s binge session.”

According to the Kantar Brand Lift Study, 2020, ads like these have been shown to “increase[ing] unaided brand awareness by 24% and ad recall by 25%.”

Interactive Living Room

These ads are designed to “foster greater affinity with a brand” through “customizable interactivity” focused on whatever elements of your brand you would like to promote. Whether you want to get the word out about a new product launch, enhanced features of an existing product, a new line of services, a company announcement, or more, these ads make it engaging and easy. Hulu notes that they offer “select functionality via third-party producing and hosting partners,” and that the production lead time is quite a bit longer than for most ad types at “four to six weeks from the receipt of the final assets.”

Max Selector (Beta)

In this ad type, viewers are given a choice over how they would like to learn about the product or service being advertised. Interactive templates are designed to create “a more engaging and immersive choice-based ad experience.”

Branded Slate

Advertisers are given the opportunity to reach audiences before the show has even begun with Branded Slate custom title cards. These brief, static video ads feature your logo with “Presented by” text, with voiceover audio that identifies your brand as the sponsor. Hulu also offers Branded Slate ads specifically tailored to entertainment clients.

Premium Slate

This 7-second ad type is similar to the aforementioned Branded Slate ads, but allows for advertisers to include “their own video, dynamic visuals, and sound” as opposed to a static video with voiceover. If preferred, you can still opt for the voiceover to be handled by Hulu talent, but it is not required as it is with the Branded Slate ads. Hulu also offers Premium Slate ads specifically tailored to entertainment clients.

GatewayGo

These unique ads are designed with conversions in mind, bringing together “Hulu’s traditional living room video ads with action-oriented prompts and personalized offers.” GatewayGo ads harness “second screen enablement technologies such as QR codes and push notifications” by “shifting conversion actions from the TV to mobile devices.” Viewers who wish to learn more can simply scan the QR code using their phone—which is likely within reach, if not in their hand—or choose to receive notifications.

According to a 2020 Hulu Internal Study, “6 in 10 viewers like that they can discover and act on deals with GatewayGO.” For these ad types, Hulu strongly recommends 30-second placements “to increase engagement,” though the minimum required length is just 15-seconds.

Pause Ad

Pause ads are unique in that they reach viewers who have decided they are ready for a break by pressing the pause button, with the ad serving as a screensaver of sorts. These offer an ideal opportunity to reach viewers in the least intrusive way possible, and give you significant opportunity to increase brand awareness—particularly for viewers who pause often, and for longer periods of time.

Poster Marquee Ad

Want to entice viewers to watch a specific series or theatrical release? This ad type makes it possible by leveraging “existing coming soon design components to promote a trailer for an upcoming title.” Hulu recommends that these should ideally be an “extended trailer,” with 15-second and 30-second ad spots not recommended.

Cover Story Brand Placement

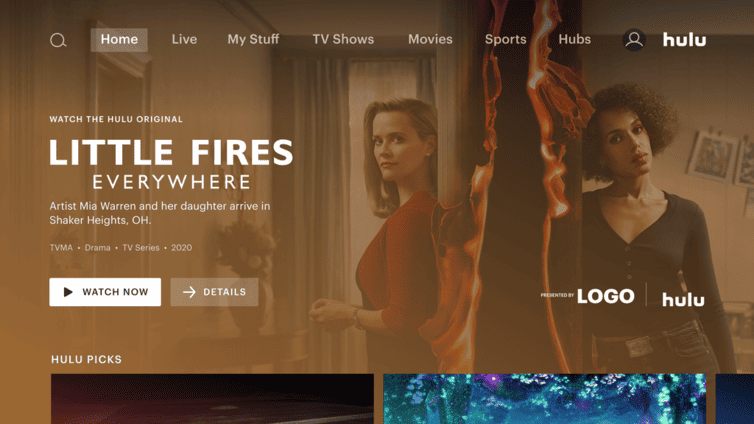

Image Source: https://advertising.hulu.com/ad-products/cover-story-brand-placement/

For this ad type, the only thing Hulu requires is your logo, which will be showcased directly within the Hulu homepage alongside the “Presented By” notation, as shown above. Thanks to their prominent placement, these ads are ideal for increasing exposure, and enhancing brand recognition.

Sponsored Collection Brand Placement

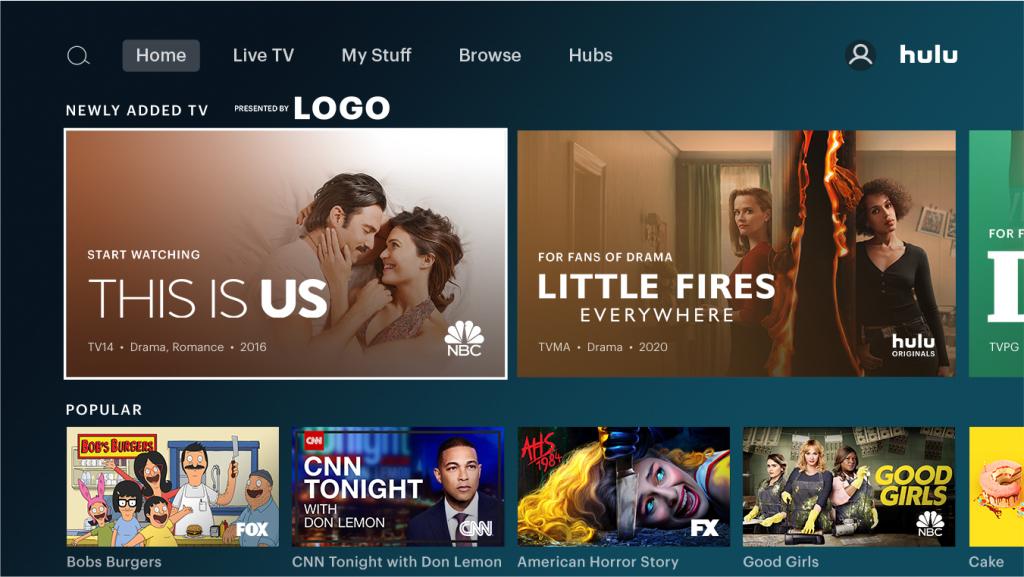

Image Source: https://advertising.hulu.com/ad-products/sponsored-collection-brand-placement/

This placement offers “advertisers extended ownership of a collection sponsorship through logo placement adjacent to content in Hulu’s UI across devices.” As shown in the above example where “Newly Added TV” programs are “Presented by LOGO” (your logo here!), your sponsorship displays in a highly visual location that naturally draws in viewers’ eyes.

Promoted Content Marquee Ad

This unique advertising option “mimics the existing Hulu UI design and only supports long-form full-length episodes or feature films.” Because “Hulu viewers already recognize this design to promote content that is available for them to watch,” they may not even realize what they’re seeing is an ad.

*Note: The ad units mentioned are almost exclusively available via guaranteed IOs (national or local) and not the audience-driven methods.

Best Practices for Hulu Advertising Campaigns

Whether you’re promoting a new product, driving subscriptions, or raising brand awareness, these best practices will help you maximize the impact of your Hulu ads and connect with your target audience effectively. Let’s explore the essential tactics and insights for creating high-performing Hulu ad campaigns.

Follow Creative Best Practices for Video Campaigns

Adhere to Ad Specs – Always adhere to the platform’s ad specifications to ensure your video displays correctly across different devices and platforms. This includes guidelines on resolution, aspect ratio, file format, and maximum file size.

Build a Strong Hook – Grab the viewer’s attention within the first 3-5 seconds. This can be achieved through visually striking imagery, compelling storytelling, or posing a thought-provoking question. The key is to pique curiosity and entice viewers to continue watching.

Consistent Branding is Key – Maintain consistent branding across your video campaigns to reinforce brand recognition and recall. This includes using your logo prominently at the beginning and end of the ad, as well as incorporating consistent color schemes, fonts, and messaging that align with your brand identity.

Stick with Simple Messaging – Focus on communicating a single, specific idea or message in your video ad. Avoid overcrowding the ad with too much information, as this can overwhelm viewers and dilute the effectiveness of your message. Keep it simple, clear, and memorable.

Use Text for Emphasis – Use text overlays strategically to highlight key messaging or calls to action in your video ad. This ensures that important information is conveyed effectively, especially for viewers who may be watching with the sound off.

Provide Variety and Freshness – Rotate your video ads regularly to prevent audience fatigue and maintain engagement. Experiment with different creative strategies, visuals, and messaging to keep your ads fresh and appealing. This also allows for A/B testing to determine which creatives resonate best with your target audience.

Utilize Audience Targeting – Tailor your creative content to resonate with the specific interests, preferences, and demographics of your target audience. This may involve customizing the storyline, imagery, and messaging to appeal to different audience segments and maximize relevance and impact.

By incorporating these best practices into your video campaigns, you can enhance their effectiveness and drive better results in terms of engagement, conversion, and brand awareness.

Use Hulu’s Targeting Capabilities Wisely

Hulu Ad Manager empowers you with a robust suite of targeting options to reach your ideal audience. Here’s how to leverage them effectively:

Audience Targeting:

- Demographics – Reach viewers based on age, gender, income, and parental status. This allows you to tailor your message to resonate with specific segments.

- Lifestyle Interests – Target users based on their interests and hobbies. For example, target fitness enthusiasts with ads for your activewear line. (Explore the full range of interest categories within Hulu Ad Manager).

- Behavioral Targeting – Go beyond demographics by targeting viewers based on their past purchase behavior or browsing habits. This can significantly increase campaign relevance.

Content Targeting:

- Genre Targeting – Place your ads within specific genres (e.g., comedy, sports, documentaries) relevant to your product or service. This ensures your message reaches viewers actively seeking content aligned with your offering.

- Programmatic Targeting – Target specific shows or programs on Hulu where your ideal audience is likely to be watching. This allows for highly focused ad placement.

Location Targeting:

- Geographic Targeting – Reach viewers within specific cities, zip codes, Designated Marketing Areas (DMAs), or regions. This is ideal for promoting local businesses or service-based offerings with a geographical focus.

Pro Tips for Smart Targeting:

- Combine Targeting Methods – Utilize a combination of audience and content targeting for maximum reach and relevance. For example, target viewers interested in fitness (audience) while placing your ads within workout-related shows (content).

- Leverage Lookalike Audiences – Expand your reach by targeting audiences similar to your existing customers.

- Test and Refine – Don’t be afraid to experiment with different targeting combinations and monitor performance metrics to optimize your campaigns for better results.

By strategically using Hulu’s targeting options, you can ensure your ads reach the right people at the right time, maximizing campaign effectiveness and ROI.

Measure and Optimize Campaigns Based on Performance

Data is king when it comes to optimizing your Hulu ad campaigns. Hulu offers advertisers varying measurement and attribution insights for their campaigns, which depend in part on how the ads were purchased. Hulu’s attribution capabilities let advertisers measure brand lift and direct ROI, and business outcomes across QSR, retail, ecommerce, tune-in, automotive, and CPG categories. Third-parties like Tinuiti offer more omnichannel campaign analysis options.

Here’s how to leverage Tinuiti’s expertise to achieve peak performance:

Set SMART Goals and Benchmarks

It’s crucial to begin by defining your objective with a clear SMART goal that aligns with your overarching marketing strategy. This goal should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound. Once your objective is established, it’s essential to establish benchmarks by leveraging historical data from past campaigns or industry averages. These benchmarks will help set realistic expectations and guide your efforts in tracking key metrics such as impressions, clicks, and conversions throughout the campaign.

Continuous Optimization

At Tinuiti, our omnichannel campaign analysis allows us to compare your Hulu campaign’s performance with other marketing channels like social media and email, giving you a holistic understanding of how customers engage with your brand across different platforms. But it’s not just about data – our team of experts dives deep, uncovering hidden patterns within the data and translating them into actionable insights.

These insights then fuel data-driven recommendations for optimizing your Hulu campaign. We might suggest adjustments to your targeting strategies, ad creatives, or even budget allocation to ensure you achieve the best possible results. We can also analyze viewer fatigue and recommend A/B testing new ad variations, keeping your audience engaged and maximizing the effectiveness of your Hulu advertising.

Putting it into Practice

After a few weeks of your campaign running, revisit your initial benchmarks to evaluate progress. Don’t just rely on surface-level data, leverage omnichannel analysis to understand what elements are resonating and which areas need improvement. This comprehensive analysis allows you to pinpoint the strengths and weaknesses of your targeting, ad creatives, and budget allocation.

By taking a data-driven approach and utilizing Tinuiti’s expertise, you can continuously measure, optimize, and refine your Hulu campaigns, driving maximum impact and achieving your marketing objectives.

Best Examples of Hulu Ads

Let’s dive into some of the most memorable and effective Hulu ad campaigns that have left a lasting impression on audiences.

Filippo Berio Interactive Ads

Image Source: https://advertising.hulu.com/brand-stories/filippo-berio/

Filippo Berio is a brand best known for their selection of olive oils and vinegars, with a legacy tracing back more than 150 years. Their thoughtful use of interactive ad formats helped them in connecting with potential customers, with their Hulu ad campaign resulting in a “2x lift in brand favorability”, and a “3x lift in brand consideration.”

- Filippo Berio’s use of the Interactive Living Room ad type “was especially impactful as an awareness-driver, highlighted by a +44% lift in brand awareness and +64% lift in message association”

- Other ad types were included in the campaign as well, including standard and situational ads

ThirdLove Contextually Relevant Original Sponsorships

Image Source: https://advertising.hulu.com/brand-stories/thirdlove/

ThirdLove is a lingerie and loungewear company that focuses on body positivity and inclusivity in their marketing, and importantly, their range of products and sizes. The brand crafted a Hulu advertising strategy that aimed to enhance “awareness and overall consideration for their products across women of all demographics” with ads that ran “alongside premium and contextually-relevant Original content.”

ThirdLove saw results that outperformed “both industry and Hulu retail norms,” in part by advertising during women-produced content, and content that focuses on themes and issues that are of importance to women. This Hulu campaign included:

- Co-branded ads at the start of every episode of Mrs. America

- Creative that included a CTA and a discount code that could be accessed by “visiting a unique URL tied to the Hulu Original series, Little Fires Everywhere”

Best Strategy for Hulu Advertising [from the experts]

Experimentation is at the heart of all statistically-significant data, and Hulu makes experimentation easy and affordable. With more than a dozen distinct ad types to choose from—and an array of ad lengths to suit all advertising needs and goals—you are provided with all the necessary tools to find the ideal methods to reach new and existing audiences.

With Hulu ads, there is no shortage of innovative options to choose from, and we encourage you to experiment extensively, but also strategically. No matter how sizable your streaming ads budget, no brand can afford to throw everything at the wall and see what sticks. But you can thoughtfully design combinations of differing visual components, and ad lengths, to see which resonate best with viewers.

These learnings can then be applied across similar streaming platforms as well, many of which won’t have the same robust inventory of options to experiment with.

According to a Nielsen CTV Analytics study, 62% of Hulu viewers never saw a brand’s ad campaign on linear TV, making Hulu a critical partner to brands trying to reach new audiences or their full target audience. And with Hulu’s ability to audience-target based on CRM matching or behavioral segments, Hulu is an important partner in delivering addressable TV at scale.

If you’re interested in advertising on OTT/Streaming TV, check out Tinuiti’s TV & Audio advertising services.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published by Tara Johnson in July 2020 and has been updated for freshness, accuracy, and comprehensiveness.

-

PPC5 days ago

PPC5 days agoHow the TikTok Algorithm Works in 2024 (+9 Ways to Go Viral)

-

SEO6 days ago

SEO6 days agoBlog Post Checklist: Check All Prior to Hitting “Publish”

-

SEO4 days ago

SEO4 days agoHow to Use Keywords for SEO: The Complete Beginner’s Guide

-

MARKETING5 days ago

MARKETING5 days agoHow To Protect Your People and Brand

-

PPC6 days ago

PPC6 days agoHow to Craft Compelling Google Ads for eCommerce

-

SEARCHENGINES6 days ago

SEARCHENGINES6 days agoGoogle Started Enforcing The Site Reputation Abuse Policy

-

MARKETING4 days ago

MARKETING4 days agoThe Ultimate Guide to Email Marketing

-

MARKETING6 days ago

MARKETING6 days agoElevating Women in SEO for a More Inclusive Industry